Doing Business Bhutan

Past — What and Why?

Whilst 4,500km apart, from Tashichho Dzong in Thimphu to Parliament House in Singapore, the Land of Thunder Dragon and the Lion City are both small countries sandwiched between the geopolitical realities of large neighbours (one landlocked, one sea-locked; one known for prosperity, one for happiness). Not surprisingly, the socio-economic landscapes are intractably linked to the ebbs and tides of the neighbours and the larger world beyond.

Often reminded, The Little Red Dot, Singapore catches a cold when the bigger boys sneeze. Drukyul (The Land of Thunder Dragon) is similarly not immune. Likewise, there is a Bhutanese saying-when two elephants fight or make love, the ant in the middle is squashed.

From this perspective, there are parallels to the Singapore narrative — particularly in improving business climate to attract financial, technology, and human capital — that could be ideas for Bhutan’s drive to take greater charge of her socio-economic destiny.

Leaders of the two countries have long enjoyed a warm and friendly relationship, with frequent bilateral exchanges and dialogues at the highest levels of government. It is no secret that the Bhutanese leaders have strong admiration for Singapore’s founding leaders and economic progress, and conversely, there is much for a young nation like Singapore to learn from centuries of ancient Bhutanese wisdom.

Since the first direct Paro-Singapore flight landed in Changi on 1 September 2012, interaction between the people and businesses has steadily increased. Singaporeans are among the top visitors to Bhutan each year (about 4,500 in 2017). More Bhutanese have also started to study, work and holiday in Singapore.

This article is not just about Doing Business In Bhutan, but Doing Business Bhutan, taking into consideration the connectedness of Bhutan today with the world at large — the economies, the people, the cultures — and the opportunity for Bhutan to do business with the global economy in a multi-lateral, multi-flow, multi-verse view.

Drawing on the Singapore experience, as a child growing up in post-independence Singapore, I remember television as a communal black-and-white evening affair at a community centre, and a telephone as a luxury we borrowed through the kindness of richer neighbours. Food, while available, was simple, and yet we finished every grain in our worn and chipped bowls.

In those early days as a small island trading entrepot, with trade at three times of Gross Domestic Product, Singapore had a key survival imperative

— attract more trade. More trade meant more income, more jobs, more bowls of food. Simplistically, by being better, faster, and cheaper. After experiencing her first recession in 1987, Singapore launched the world’s first National Single Window project in 1989 — a system that integrated import, export and transhipment documentation processing procedures, and enabled the government agencies, trade and logistic communities to fulfil their regulatory requirements and trade formalities at a fraction of the time and costs it took previously. Instead of days, approvals are within 15 minutes on average, with costs significantly reduced at the same time.

It is instructive to share that leadership and ownership at the highest level of government were critical for Singapore’s success for this first national initiative: Leadership in the form of leaders with vision and commitment towards the sustainable long-term economic and social development of the country, and ownership in the form of government/semi-government entities empowered with the mandate and authority to drive — or put bluntly — to cut through government bureaucracy, and to herd different stakeholders towards a common destination.

There were leaders who drove the harmonisation of policies, standards, inter — operability, regulations, guidelines, frameworks — all critical in the overall successful implementation, across multiple ministries and agencies, in achieving a holistic outcome that made socio-economic sense for Singapore.

Now — What and How?

Along with this imperative, Singapore developed many other business climate improvement initiatives and projects to stay ahead of competition, including the belief that Singapore must make herself so inexcusably appealing that investors have no reasons not to invest in Singapore, or if that failed, at least attractive enough to do business with Singapore.

Doing Business Singapore was, and still is, a key tenet of our economic policies, with multiple government agencies working not only to increase the inflow (foreign enterprises setting up in Singapore) but also to expand the outflow (internationalising Singapore enterprises).

Information Communications Technology, or Infocomm, was used as a strategic tool to support this key tenet in nation-building. Starting with the Civil Service Computerisation Programme in 1981, Singapore went through multiple refresh of Infocomm Masterplans to build capacity, competency, and connections across the government, the businesses and the citizens-to work, live, learn and play in an inclusive digital society.

Then, we started with 850 who knew what a computer was. Today, we have more than 150,000 Infocomm professionals and a robust Infocomm industry which contributes over 6.5 percent of Singapore’s Gross Domestic Product.

Notable Doing Business initiatives include BizFile, which allowed online business filing and registration, and Online Business Licensing System (OBLS) in 2005, which allowed businesses to apply for multiple business licences conveniently within a single portal. Both BizFile and OBLS are multi-award recipients from world multilateral organisations. Singapore holds the record as World Bank’s No 1 Ease Of Doing Business Country for 10 consecutive years.

Launched three years ago in 2015, Licence One is the new government-wide one-stop business licensing portal that delivers a more user-friendly and efficient licensing experience for businesses. It simplifies the application and payment of licence-related fees and allows businesses to apply for multiple licences simultaneously, plus the updating, renewal and termination of over 120 licences across more than 20 government agencies 24×7 at their own time and convenience.

The businesses greatly benefited from productivity gains and better ease of doing business, with instantaneous approvals and a single 360 view of all their licensing interactions, whilst the productivity of government officers is further enhanced with automated approvals of licence applications: Efficiency, transparency, convenience.

At this point, I would like to caution that success in Doing Business is not merely about technology. It is about a singular shared mindset, a holistic one-government approach that includes political boldness to execute beyond will, governance structures with regulatory agility, realistic financial and tax regimes, civil and administrative service adaptability, commercial and industrial participation, inclusion and education of citizens, residents and visitors, etc, that characterises an attractive Doing Business country.

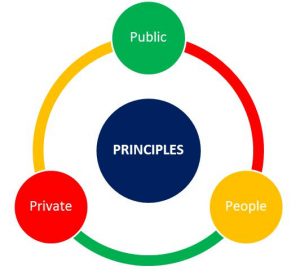

I would frame the Doing Business journey as the 4 Ps — Principles (Central), with Public (Government), Private (Businesses) and People (Citizens, Residents, and Visitors).

Principles: What are the core Doing Business principles that guide each policy, regulation, rule? What are the clear, measurable, desired outcomes of these core principles? Why these core principles?

Public: How ready is the government to create an environment for Doing Business to be so easy, so convenient? Is there capacity in the government to lead, to seed, to nurture the different components and stakeholders? Are governance structure, plans, and processes ready?

Private: What is at stake for the companies and the entrepreneurs? Have their commercial needs been considered in each policy, regulation, system? How sustainable and practical is it for the businesses, that is, what’s in it commercially for the private stakeholders?

People: How have the views of the city been heard? Are the views representative across the different segments and groups? Similarly, are these views considered in each policy, regulation, and system?

Framework – 4Ps of Doing Business

Tightly coupled, the 3 smaller Ps (Public, Private, People) provide the complementary support and competitive tension in weaving a strong and compelling ring of common goals, competencies, and capabilities in driving the Doing Business objective.

In Bhutan’s case, one would also expect Gross National Happiness (GNH) to be within the large P (Principles), which provides the guidance and direction towards collective happiness and well-being of the people in the Land of Thunder Dragon. This would in turn drive the other 3Ps, in the Doing Business initiatives, to consider not only raising Living Standards and Good Governance, but also Ecological Resilience, Cultural Diversity and Community Vitality over the long-term.

Future

As someone who was extremely privileged to have interacted with many government and business leaders in Bhutan, and having been personally involved in multiple infocomm projects, I sense a very strong desire in Bhutan to digitally transform the nation, albeit on its own terms.

I believe Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness goals are not incongruent with the pursuit of Gross Domestic Product. They are in fact both sides of the same coin. Like a campfire that provides light, warmth and heat, the light allows us to see what’s important, the warmth to keep us warm, the heat to make that Ema Datse dinner. Improving Doing Business is not, and should not be, the end-all and be-all in Bhutan’s economic development. Economic development is important but Bhutan needs to take into account what will work, or not work, relative to Bhutan’s culture, history and readiness.

Skip the manufacturing and factories, where physical movement of resources into Bhutan, and the shipment of finished goods out of Bhutan, make it a challenging business model. Focus on Bhutan’s natural advantages-pristine habitat, clean power, sustainable practices, educated young population, energy and creativity of the people, the wisdom of centuries of traditions.

The advances in information technology and telecommunications have allowed the growth of disruptive business models (think Uber, AirBnB, Amazon) and are which, IMHO (In My Humble Opinion), dis-intermediated market models that Bhutan can draw on to deliver distinct value-added businesses virtually, remotely, seamlessly, and cleanly.

These advances also help Bhutan overcome the tyranny of a landlocked nation. Virtual access, via a mobile phone or a laptop, is in today’s digital world often more critical, more interconnected, and more efficient than the physical world of roads and bridges.

It is to Bhutan’s advantage to leverage this new flatter world economy, where businesses are often direct seller-buyer, bypassing the middlemen of ages past. Instead, think creative, financial, education, infrastructure services — in short, be a market-maker rather than just a market. Serve not just the Bhutan market, but the markets nearby and the world further afar. Think intellectual property. Think crowd-sourcing. Think co-creation. Think use, not build. Think technology-as-a-service. Think cloud. Think public-private-partnerships. Think crowd-funding.

Every country needs to continue to re-invent itself in all aspects of nation-building-to learn, to adapt, to grow. There is no end point as in “we’ve arrived” but a continual process of learning, adaptation and growth. This is the same for Bhutan as it is for Singapore, especially if we wish to be plugged-in and relevant in the new digital world.

As a wise and dear Bhutanese friend shared with me on my first trip to Drukyul, “Life is not a puzzle to be solved but a journey to be lived.”