Large-scale Innovative Fund Raising for Greater Impact and Sustainability of CSOs

Introduction

Sustainable financing is one of the major challenges faced by many civil society organisations (CSO), particularly in developing countries where the need for CSO engagement is even greater. Although civil society vis-a-vis community participation is not a new concept in Bhutan, the prevailing western notion of non-governmental organisation (NGO) and its organisational framework is fairly new to the Bhutanese populace and institutions. Besides other areas of transition, Bhutan is also witnessing a quiet but profound change in the perception of the relationship between the government and its citizens. With the advent of planned development in the early 1960’s, the government successfully championed its role as a provider of modern development services for more than half a century. Now with the rapid transition to a democratic form of governance, private institutions and citizens at large are increasingly viewing the role of the government, not just as a provider but more as an effective enabler and facilitator of development.

Civic space, therefore, will have to play an instrumental and effective role in nation building by complementing and supplementing the efforts of the government to enhance inclusive development and provide alternative voice and checks wherever necessary. This is truly an exciting period in Bhutan’s development journey. Most fundamentals for realising the development vision of Gross National Happiness (GNH) are well placed and embedded across all facets of development in the country. Close to 60 percent of the population are under the age of 30 with a youth literacy rate of over 86 percent1. Bhutan has free trade access to one of the largest markets in the world and is rated 27th least corrupt nation out of 175 countries in the World Corruption Perception Index by the Transparency International2, making Bhutan a potentially attractive destination for foreign investment.

The strength of the civil society in any nation mirrors the openness and progressive nature of the nation state and its society in general. In a progressive democracy, the role of the civil society is paramount to ensure greater transparency, participation in decision making, addressing issues of equity, and providing necessary checks and balances for the greater good. December 17, 2016, marked an important milestone in the journey of the CSO movement in Bhutan when His Majesty The King awarded the National Order of Merit (Gold) to 22 prominent CSOs representing various causes across the nation. The historic national event clearly signalled the need to embrace and recognise the role of the CSOs in the country and inspired all who were engaged in various CSO activities across the country.

The Evolution of Civil Society Organisations

Civil society is generally considered as the third sector of society representing the collective will and interests of the non-governmental section of the society. Aristotle refers the term civil society as a “community” characterised by a shared set of norms and ethos under which free citizens aspire to live equally under a progressive rule of law.

There are many definitions of civil society but, fundamentally, it represents the “space” outside of the government and private sector that is inspired by universal values of equality, driven by a strong sense of volunteerism and purpose, representing a wide array of non-governmental and not for profit organisations. However, with changing times and blurring of boundaries between organisations, sectors, states, and investments, the role and perception of civil society is also evolving in so many ways, some not necessarily desirable.

The World Economic Forum3 best describes the evolving nature and role of civil society in this globalised world. “Civil society is recognised as encompassing far more than a mere “sector” dominated by the NGO community: civil society today includes an ever wider and more vibrant range of organised and unorganised groups, as new civil society actors blur the boundaries between sectors and experiment with new organisational forms, both online and off.” The new role is also reflective of the changing political, economic and social context around the world. Technology and Internet are disrupting the flow of capital and investments and all forms of new media are dramatically changing social engagement at scales never witnessed by human history.

The rapidly evolving role of the civil society presents both opportunities and challenges amidst rising integration of global markets and increasing participation of the masses in political and governance discourse. For developing countries such as Bhutan, the challenges and opportunities of CSOs are even more pronounced and significant from many aspects.

The enactment of the Civil Society Organisation Act4 of Bhutan in 2007 was aptly timed and provided the legitimacy for Bhutanese citizens to nurture the civic space within a proper framework of governance and rule of law. The introduction of the decentralisation policy in 1981 was another milestone in nourishing and promoting the culture and organisational capital of CSOs across Bhutan. With a literacy rate of over 63 percent, civic engagement in Bhutan is comparatively progressive and active in many respects. Several CSOs have a very good track record in promoting their causes and have also been recognised by both global and local organisations for their achievements and work in Bhutanese society. Particularly, within the overall framework of democratic governance, the need and the role of CSOs are increasingly recognised and appreciated in providing the much needed space and mechanism to partake in various development services and contribute towards the growth of social and intellectual capital in the country.

Project Finance for Permanence – an Innovative Mechanism for Large Scale Conservation Fund Raising

Although there are several issues concerning the management and growth of the CSOs in Bhutan, this paper will focus on presenting the broader opportunities for large scale fund raising using the “project finance for permanence” approach as an innovative and sustainable mechanism for financing large scale conservation and related programmes. Most CSOs in Bhutan are faced with increased challenges in securing sustainable financing of their activities particularly from domestic sources. Fund raising has been limited. The funding data clearly indicates that most CSOs have not been very successful in raising adequate funds for their activities, particularly in the social sector. The reasons are varied- ranging from constraints of capacity to a serious lack of resources as well as fund raising and networking skills.

Project Finance for Permanence (PFP) is an innovative and sustainable financing mechanism adapted from a common “Wall Street” practice known as “project finance”, designed primarily for large-scale projects that requires leveraging different sources of funds and partners for long term investments in various sectors. The vision of permanence and sustainability is at the heart of the PFP approach. It seeks to achieve a long term permanent solution by ensuring resilient and adaptive processes of management and implementation. Because planning cannot anticipate every conceivable challenge that a large project may face, the PFP approach aims to create a strong foundation for implementation and subsequent management that is able to adapt and overcome unforeseen circumstances and events.

The process of securing permanent protection begins with the development of ambitious programmatic goals, followed by the development of a comprehensive conservation plan with well thought out milestones to achieve the desired goals at various phases. Thereafter, a rigorous financial plan is created to ensure its sustainability and lasting success. Different donors, both private and multilateral, then commit their funds to bring the plan to life. However, the funds are held back until the total fundraising goal is reached and all key legal and financial conditions that have been agreed upon are met. This mechanism is described as a “multi- party, single closing” approach. This methodical process of developing a large scale project provides donors with an up-front guarantee that their investments will be put to best use. All the project partners then come together to sign one single agreement. At this closing, often referred as launch, their donations are put into a fully registered fund, permanent or sinking in nature (Figure 1.), the governance and legitimacy of which is defined by a legally and technically vetted rules of procedure, jointly agreed by all the parties involved. Money within the fund is distributed over a set period of time and in accordance with the agreed financial and disbursement plan.The local CSO partner or government in the country where the conservation activities are to be implemented increases it’s spending until it can fully put in place an effective sustainable domestic financing mechanism to fund all the activities thereafter.

Fig. 1: PFP: A Transition Fund Model

Sustainable Financing Solution for Protected Areas

Protected areas, including community conserved areas, heritage forests, and other forms of wilderness areas are the backbone of ecosystem and biodiversity conservation. The ecosystem services provided by these large tracts of protected areas contribute immensely to human livelihoods and well-being as well as protection from the impact of natural disasters. Many empirical studies have now clearly shown that their role in helping mitigate and adapt to climate change is immensely critical and significant. It has been estimated that the global network of protected areas stores at least 15 percent of terrestrial carbon5. However, most of the world’s protected areas are under significant stress, and these stresses are worsening as both the global population and per capita consumption increase dramatically worldwide.

Despite a growing understanding of the importance of protected areas to conserve biodiversity; store and sequester greenhouse gases, and provide income, fuel, water, and food for more than a billion people worldwide, their protection and management are extremely underfunded. It is estimated that US$ 2.5 billion (Figure 2.) is needed annually to properly manage existing protected areas within developing countries alone, but only US$800 million or less is raised annually for the conservation of some of the world’s most diverse and ecologically rich protected areas. To achieve the full potential of protected areas and ensure its sustainability and protection, they need to be well designed, properly managed, politically supported, and most importantly, sustainably funded.

Fig. 2: Annual Global Protected Areas Funding Status for Developing Countries

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and its partners are using this innovative and sustainable funding approach to mobilise the stakeholders, resources, institutional commitments, and other conditions needed for successful and permanent conservation of priority protected areas around the world. WWF and a diverse group of other funders—public, private, national, and international—are implementing a number of global PFP initiatives. The first of these initiatives was the “ARPA for Life” (Amazon Region Protected Areas) project in Brazil.

The Amazon rain forest, often referred to as the “lungs of the planet”, covers much of the northwestern Brazil extending into Columbia, Peru, and other South American countries. It is the world’s largest tropical rain forest, well known for its biological diversity. It covers an astounding area of 5.5 million sq. km, almost nine times the size of France, storing 2.2 billion tonnes of carbon and is home to 40,000 species of plants, 427 species of mammals and 1,294 species of birds. The Amazon forests are the largest contiguous stretch of rich and diverse tropical rain forests and 60 percent of these awe-inspiring landscape is within Brazil.

Unfortunately, these forests are not immune to the destructive practices of the modern day development process. Over the last decade an average of over 8,100 sq. km of prime and pristine amazon forests are lost to deforestation and cattle ranching every year. Although the Brazilian government is committed to protecting the amazon forests, competing priorities for providing livelihood for millions of poor communities dependent on the forests are taking precedence over conservation.

In 2014, the government of Brazil, WWF and a diverse group of partners from the public and private sector announced a new US$215 million fund to protect a 60-million hectare network of protected areas in the Amazon region of Brazil. This PFP initiative guaranteed the financial sustainability for one of the largest protected areas network in the world. The two other completed PFP deals were the “Great Bear Rainforest Project” in Canada and “Costa Rica Forever” in Costa Rica. The former resulted in a fund of CDN$120 million to protect 8.5 million hectares of coastal British Columbia temperate rainforest. The latter raised US$57 million from private and public donors outside of Costa Rica to protect 1.3 million hectares of terrestrial habitat and 1 million hectares of critical marine habitat. The “Costa Rica Forever project set the stage for Costa Rica to become the first developing country in the world to meet the UN/CBD standards for protected areas management6.

Bhutan for Life Initiative: The First PFP in Asia

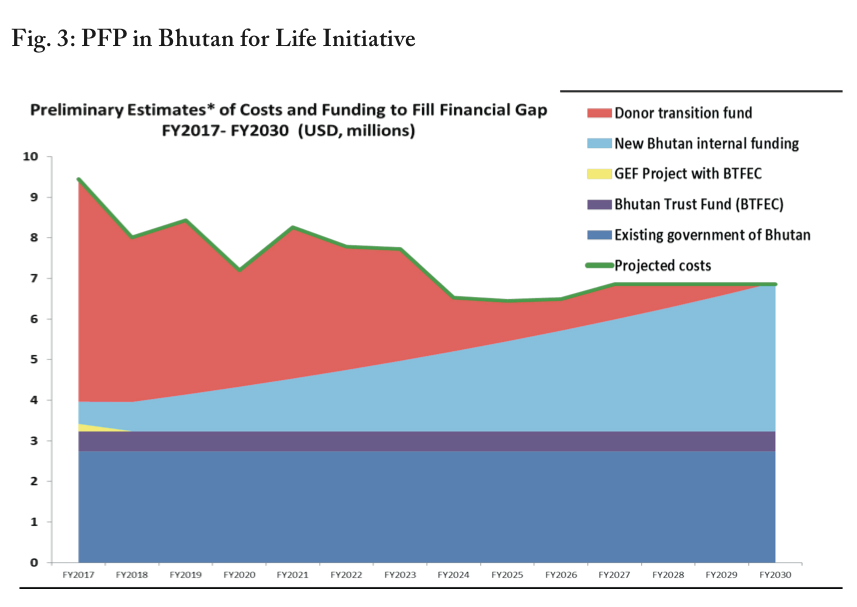

An ongoing PFP programme in Bhutan is the Bhutan for Life (BFL) (Figure 3) project, led by the Royal Government of Bhutan (RGoB), WWF, and partners to raise US$40 million (Nu 2.6 billion) to effectively manage and permanently secure Bhutan’s 52 percent protected areas over a 14-year time horizon. BFL is the first PFP project in Asia and is expected to raise the much needed awareness in the region to protect the last remaining critical ecoregions of Asia.

An ongoing PFP programme in Bhutan is the Bhutan for Life (BFL) (Figure 3) project, led by the Royal Government of Bhutan (RGoB), WWF, and partners to raise US$40 million (Nu 2.6 billion) to effectively manage and permanently secure Bhutan’s 52 percent protected areas over a 14-year time horizon. BFL is the first PFP project in Asia and is expected to raise the much needed awareness in the region to protect the last remaining critical ecoregions of Asia.

Bhutan for Life is also an innovative funding initiative that aims to provide a sustained flow of finance to maintain the nation’s protected areas and biological corridors in perpetuity. The goal of BFL is to mobilise, in a single agreement, all the government financial and other commitments needed to fully develop Bhutan’s protected area system and maintain it in the foreseeable future. There are two key components to BFL: one is the multi-party, single closing deal that closes only after certain conditions are met and all funds are committed;the other is a transition fund. After the closing, donor funds are placed in a public-private transition fund that is invested locally and globally, that makes annual payments, starting high and receding to zero over a projected period of 14 years, at which stage the government picks up all the costs of managing the PAs from its own internal resources, thereby putting in place a truly sustainable and self-reliant funding mechanism within the country.

Application of Project Finance for Permanence in the Social Sector

The achievements that these conservation PFP initiatives have accomplished in mobilising unprecedented resources and commitments to launch extensive protection can make us believe that the PFP approach can be applied in other fields as many of the principles that work in conservation may be similarly beneficial for other large-scale social sector initiatives, particularly for smaller and progressive countries such as Bhutan where chances of success are much greater.

In the case of Bhutan’s social sector, civil society sector could specially benefit by applying project finance principles to address the perennial issue of funding and accessing funds in a more innovative and attractive method. PFP is not only just about funding. It is also a means for inspiring governments and non-government organisations to commit to effective and enduring vision for programmes for the common good that are usually underfunded. PFP allows for financial leverage that magnifies the effect of each funder’s contribution through the closing and, therefore, from a private donor’s perspective, such deals can leverage bigger investments from various sources and thereby ensure higher returns in the form of “on the ground” conservation and social impact. For CSOs, such partnerships and the process of raising large-scale funds can provide the much needed resources for the sustainability of some of their core programmes on a long term basis.

PFP also coordinates the many entities typically needed to achieve a large-scale vision by establishing a multi-stakeholder process known as the “multi-party, single closing” that benefits all involved. Adopting this critical component of the PFP mechanism would encourage CSOs to work together with the government, private donors, multilateral agencies, and other partners to mobilise in a single agreement, all governmental, financial, and other commitments, needed to accomplish an initiative that requires a significant funding for long-term viability.

Conclusion

Civil society organisations fulfil very important tasks and complement roles of the governments as they often have better comparative strength and network to implement the development activities. They perform such tasks very effectively, often at much lower costs and with a greater sense of ownership and partnership with local people and other stakeholders. Bhutanese CSOs, despite their infancy, have made significant contributions to nation building and the evolving role of CSOs, in the light of changing political and socio-economic context, render greater opportunities for their engagement and participation. The perpetual issue of sustainable financing faced by CSOs need a new outlook beyond the traditional practice of fund raising. Financial resources accessed through piecemeal approach often keep the organisation worried and distant from long-term sustenance. Exploring “innovative and nontraditional sources of financing” for sustainability and permanence similar to the PFP approach would be a worthwhile undertaking for financial sustainability of CSOs.

Although the PFP approach was employed as a sustainable funding mechanism for large-scale conservation programmes in Bhutan, the principles that work in conservation could be equally beneficial for social sector initiatives. Besides, the PFP approach can provide CSOs much needed leverage and encourage collaboration amongst relevant organisations and sectors to overcome challenges and optimise scarce resources for achieving greater outcomes at scale. The important preconditions of the PFP approach that specifically focus on the need for a sufficiently strong institutional base upon which to build a sound organisation and, most importantly, strong political support and good governance besides potentially attractive projects, provide both challenges and opportunities to CSOs. The PFP approach which integrates the vision of permanence with a robust process offers a holistic and practical avenue to solving the world’s pressing problems in an innovative and coordinated method. It is a bold initiative with a powerful vision and an equally powerful approach.