Nationalism in a new republic

You can download this Article as a PDF by clicking here

“A yam between two stones” is how Nepal’s founding monarch, Prithvi Narayan Shah, described the unified kingdom he forged out of dozens of feuding Himalayan principalities in the 18th century. Even back then, it was evident to the king that his new nation had to contend with the geopolitical influences of its two powerful neighbours china to the north and British India to the south.

Fast forward 250 years, and the first elected prime minister of the Republic of Nepal and former guerrilla commander Pushpa Kamal Dahal aka Prachanda paraphrased the king to say that Nepal was actually a “dynamite between two boulders”. He was trying to play India off against China (unsuccessfully, it turned out) and meant that it was he, and he alone, who could ensure stability in the Himalaya.

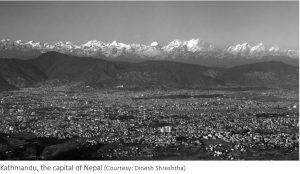

Nepal is the most vertical country on earth, the terrain rising from 150ft above sea level on the border with India in the south to nearly 30,000ft on its northern border with China, all within a horizontal distance of only 80 miles. It is this altitude variation that gives Nepal its stupendous scenery, biodiversity and rich ethnic mixture – which is perhaps why the country has always been practically ungovernable.

The East India Company invaded Nepal in 1814, but pulled back after cutting the country in half because the British figured it would be just too much trouble to conquer it. When Nepal invaded Tibet in the 19th century, the Chinese came to the rescue and chased the Gorkhali Army nearly all the way back to Kathmandu. They took one look around, found the country too inhospitable, and went right back.

It is because everyone left us alone that Nepal today is the oldest nation state in South Asia. It was a warlike and expansionist kingdom, and the British thought that it was better to leave Nepal as a buffer state as long as they could recruit the fierce Gurkhas into their army. So, while colonialism meant that other parts of the subcontinent got infrastructure, education, medical care, a justice system and institutions of democracy, Nepal was ruled by feudal kings who closed it off from the outside world.

Nepal may have been independent, but the isolation kept it in the middle ages. By the 1950s, when the British left the subcontinent and Nepal started opening up to the world, it had no roads, few schools and hospitals and no democratic tradition. But what Nepal had was a deep sense of nationhood. The Nepalis were poor, but they were proud to be Nepalis.

Today, the world’s most densely populated mountain nation in the world is confronting developmental, economic and political challenges of opening too rapidly to the outside world. Despite a ruinous Maoist insurgency and the chronic fecklessness of its rulers, Nepal however, has taken dramatic strides since 1990 in reducing poverty, and meeting the United Nations targets for health and education. The key to this achievement has been grassroots democracy that brought up elected local leaders accountable to the people. Nepal is living proof that decentralised democracy delivers development.

An elected Constituent Assembly is now trying to draft a new constitution that will devolve power to federal provinces, and give a voice to ethnic groups and those traditionally excluded from political decision-making. One of the contentious issues delaying constitution-drafting is the question of what constitutes Nepal’s national identity.

The country is located at the crossroads of civilisations, and has 123 ethnic groups ranging from aboriginal dwellers of the Tarai lowlands, settlers from the Indo-Gangetic plains, and waves of migrants from Tibet. They speak more than 95 languages and dialects. Ever since Prithvi Narayan Shah brought them all together into a nationstate called Nepal, the monarchy has tried to forge a national identity.

In 1960, after taking over absolute power in a coup, King Mahendra laid down the attributes of a unitary state: Nepali as the national language, the daura suruwal as the national dress and Hinduism as the national religion. Mahendra himself wrote the lyrics for songs that extolled the traits of Nepali nationalism. Because of the role of his forebears in founding Nepal, Mahendra saw the monarchy as an inalienable symbol of Nepali nationhood.

In 1960, after taking over absolute power in a coup, King Mahendra laid down the attributes of a unitary state: Nepali as the national language, the daura suruwal as the national dress and Hinduism as the national religion. Mahendra himself wrote the lyrics for songs that extolled the traits of Nepali nationalism. Because of the role of his forebears in founding Nepal, Mahendra saw the monarchy as an inalienable symbol of Nepali nationhood.

With the abolition of the monarchy by an act of the elected Constituent Assembly in 2008, it has suddenly become politically incorrect to hark back to the Mahendra-era symbols of a unitary state. Nepal’s ethnic minorities and those excluded from national life are now demanding new definitions of Nepali nationhood. The emphasis is on unity in diversity, a pluralistic society that is comfortable with multiple identities which does not see the need to artificially set parameters based on one dress, language, religion or culture.

In 2008, many in Kathmandu feared that with the unifying monarchy gone, Nepal would crumble and fragment. In fact, it did not even take a year for most Nepalis to forget the last king, Gyanendra. Or that the country was ever a monarchy. Recent public opinion polls have shown that the monarchy is seeing a resurgence in popularity, but that has more to do with public disillusionment with bickering politicians who can neither write the Constitution, nor govern.

On the streets of Qatar’s capital, Doha, every fifth person you meet is a Nepali. Nearly 20 per cent of Nepal’s population at any given time works abroad ± mainly in the Gulf, Malaysia and India. It is when meeting Nepalis abroad that one gets the most direct proof that the Nepali identity is intact and that it stitches this diverse country together.

It is not just that a Madhesi from the Tarai or a Tamang from the mountains both have a green Nepali passport. In the absence of the monarchy and the Mahendra-era traits of nationhood, there are other less tangible ties that seem to bind Nepalis together.

One of these must be the shared language, Nepali, that is spoken by three-fourths of the people and which serves as a lingua franca. The absence of colonial rule means that English is not as prevalent, and the only way to communicate with a fellow-Nepali whether in Nepal or abroad is in the Nepali language.

Then there is the shared sense of history, of inheriting a common and collective past. This is not so much derived anymore from the glorification of Nepali generals who gallantly fought off British invaders, the pride in the legendary bravery of Gurkha soldiers in the battlefields of the First and Second World Wars, or the international fame of Sherpa mountaineers. It is not even the incongruous pride the Nepalis feel about the Buddha having been born in Nepal (Nepal did not exist 2,500 years ago) or that Mt Everest is in Nepal (the summit of the world’s highest mountain is actually shared with China).

The spirit of nationalism that stemmed from pride in our independence has perhaps been replaced with solidarity derived from collectively having to surmount common hardships. The Nepalis today are united by their resentment against successive rulers who have let them down through neglect, apathy and bad governance. It is as if the Nepalis are saying: we are all in the same boat, so we will sink or swim together.

It is the tragedy of modern Nepal that it is our collective struggle to survive that joins us most tightly today.

There are many reasons to be a short-term pessimist about Nepal. But as long as this sense of nationhood and cohesion is intact, one cannot help being a long-term optimist.