Political Parties in the 21st Century

How to Address the Challenges?

Once upon a time

My mother was born into a social democratic family, just like her father. She had been a party member since she was old enough to vote, and she voted for the party in every election. I once asked her if she had ever considered voting for a different party. “Never!” She told me. To her, this would be like committing heresy.

Later, she admitted that there had been a few elections where the positions of her party were not exactly what she wanted. However, when she was in high school, her father had told her that there would be difficult moments, when she would be in doubt. This was only natural, but it would never be a good enough reason to leave the party or vote for another. Once a social democrat, always a social democrat!

It was different with my father. He grew up on a middle-sized farm, and his father had been a member of the farmers’ party, — the Liberal Party — since he was old enough to vote. He ran successfully for a seat in the Rural Council, where the Liberal Party had a confident majority, and he was elected Chair several times.

Maybe, if my father had stayed on the farm and decided to become a farmer, he would also have become a member of the Liberal Party. Instead, he got the opportunity to study in the city, where he met fellow students with a diverse range of political inclinations. My sense is that he chose to vote for a different party in almost every election.

The examples of how my parents engaged with political parties half a century ago are not unique. Back then, more people than today were loyal members of a party. For many families, membership passed from one generation to the next. The ideologies of the parties were in many ways much clearer than what we see today. Different groups or classes in society tended to cluster around certain parties, like railroad workers with Social Democrats and farmers with Liberals. In general, politicians and parties were trusted and seen as key for the well-being and functioning of our democracy.

Loss of Confidence in Political Parties

Today, the position of the political party as a key institution of our democracy, trusted and supported by the majority of citizens and voters, is under threat. Opinion polls in many countries seem to tell the same story of politicians and parties being among the least trusted in society.

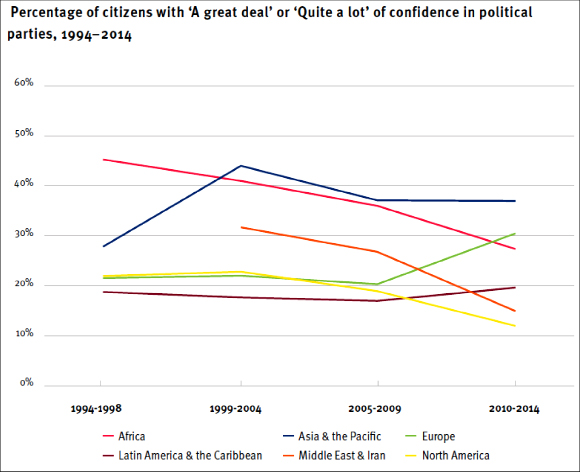

Levels of trust vary from country to country, and from region to region, with North America at the lowest level of all right now, and Asia and the Pacific at the highest, which might come as a surprise to some. See the graphic presentation below1.

The specific reasons for the low levels of trust differ between countries and regions. However, some of the explanations are rather simple and straightforward, despite parties and politicians being different. We see unrealistic promises presented during election campaigns, with very little will, ability or possibility to deliver. We see examples of how politicians use politics as a platform to enrich themselves. All around the world, we see huge amounts invested to get parties and politicians elected, and it is not always clear where the money is coming from. Citizens get the sense that if you have enough money, you can buy your way into the offices of government.

All of this contributes to the loss of confidence in the important role political parties must play in a democracy, and I agree that there are plenty of examples of parties and leaders acting in blatant disregard of principles of honesty, truthfulness, transparency, and accountability.

However, we should not forget that the reality in which political parties operate today is fundamentally different from the days of the 19th century, when the modern version of a political party was “invented”. In particular, we have seen the processes of urbanisation, modernisation, and globalisation (some might add “westernisation”) create a lot of wealth and progress, as well as a lot of new concerns.

In fact, the nation state is no longer the only well-known territory that political parties have to understand and control. They have to understand the global issues that affect the nation state. Most of the legislation presented to the parties in the Danish parliament reflects our membership of the European Union. Some legislation is shaped by our participation in global partnerships on trade and climate change, or by membership of the United Nations.

Political parties and politicians consequently do not have the level of “control” offered by the nation state characterised by a crude 19th century class society. The reality is that the individual party and the individual politician today are less influential than was the case decades ago. When citizens realise that their representatives have less control, power and influence over the nation state than they thought, they naturally get frustrated and maybe even angry. A logical reaction can be to criticise the traditional political parties for not doing their job! The next step could be to vote for a new party that offers convincing solutions to complex situations (like the global economic crisis, international terrorism or the waves of refugees), although the “old” parties and politicians would see these solutions as simplistic.

I emphasise this because I believe that a revival of the political party as a trusted and respected institution in liberal democracies must rely on a realistic understanding of the world we presently live in, and not the world we would like to live in. This is not an easy challenge! If parties expect to attract members, — and more members are necessary for parties to have legitimacy — they have to understand that the notion of “membership” is different today from what it used to be.

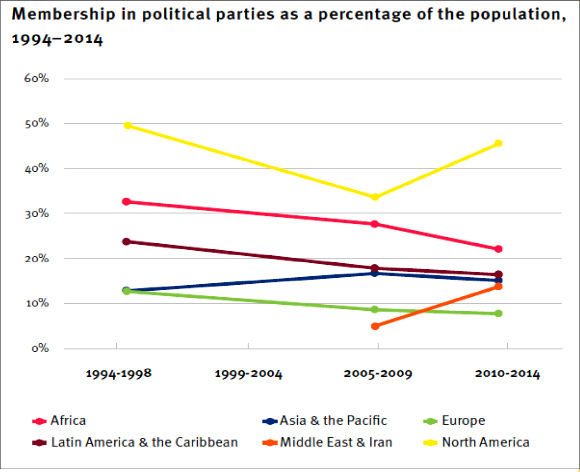

The downward trend in membership of political parties is often (and correctly so) used as an indicator of the erosion of importance and trust of parties, not least in the case of Europe, with many old-style parties rooted in the 19th century political reality.

However, as reflected in the graphic presentation above2, the birthplace of the modern political party seems to be doing worse than parties in other regions. While an average of 4.7 percent of citizens have joined a political party in Europe in 2010-2014, the global average is 14 percent, with levels in Africa and Latin America surpassing the global average. In North America and the Middle East, the numbers have even increased.

Democratic Functions of Political Parties

Before we move from the rather gloomy descriptive phase of the difficulties facing political parties, we need to look at the key functions of a political party. When we have established the rationale for these functions, we can more productively look at what political parties need to do to reclaim their role. Here we have to remember that the present debate is far from new. In fact, the critique of political parties for not delivering in reality what we believe in theory they should be able to deliver, started decades ago.

The academic research and literature on the role and functions of political parties is rich. I prefer a five-point framework3, because I feel that it combines the aspects of ideology and representation with the important capacity to govern. I will present each component with an indication of the major sub-components.

- To mobilise citizens must be a major concern for every political party, new or old. A critical mass of members is required to provide the financial support for the party infrastructure (staff, offices, outreach capacity and analytical capacity); members are also necessary to help mobilise the electorate during campaigns. A party therefore needs to consider its local level outreach, both the means of communicating through social media, and the need to be physically present in local branches around the country.

- To aggregate interests is about the ability of a party to assess the interests of the population in general, and to understand the major interests during election campaigns in particular. Large parties with members all across the country will have an advantage over small parties that may have a few strongholds. Big parties will normally also have more resources (money) to invest in expensive surveys that can help assess the various interests, and even more importantly, decide to prioritise which interests are more important.

- To recruit candidates to run for a seat in parliament, and ultimately government, is the task citizens and media often seem to be most interested in, because we increasingly live in times when personalities are given more attention than policies. What we forget is that it can take years of hard work before a candidate is mature enough to go public and compete in an election. The grooming of a candidate involves practice in how to present a policy, speak in public, and debate with others. To begin with, the candidate will often operate at the local branch level, until she has matured enough to step up to the national level. This really requires strategic planning. Rarely will a candidate rise from the unknown and become a hit overnight. It can take years of hard work.

- To develop policies is essentially about the ability of a party to take the process of aggregating the interests identified through surveys and membership inputs a step further, and develop specific policy proposals that are clear and convincing enough to win an election. Some parties do this in a centralised and top-down manner, while others involve all the levels of the party from bottom to top. One important aspect is for the party to make sure that the policies developed to respond to the urgent challenges defined by the electorate are in line with party ideology as defined in the party programme.

- To collaborate with other parties is an important function and ability in most political systems, but of course more so in multi-party systems than in two-party systems. In a proportional electoral system like the one we have in Denmark — with presently nine parties represented in parliament — we know that one party will never get enough votes to have a majority. Any party wishing to form a government knows that it needs the support of one or more of the other parties, and this therefore requires a certain degree of humility and willingness to compromise. No party is of course particularly happy about this, and it can be extremely difficult to explain to members, voters, and the media why the party has compromised here and there and maybe a little bit everywhere. This is therefore something the party has to consider carefully. In a two-party system, using a first past the post electoral system, there is not the same necessity for collaboration, because the majority needed to rule is there to begin with.

To summarise, these functions present the minimum requirements for a democratic political party. It needs to be able to mobilise, to aggregate, to recruit, to develop, and to collaborate. The open question is if traditional political parties can regain the trust they have lost by addressing these functions in new ways.

How to Respond to Key Challenges?

To start with, it might be useful to mention that there is presently no full agreement about the exact nature and severity of the crisis of liberal democracy in general, and that of political parties in particular. Yes, we have seen recent elections and referendums in Europe and the US cause a political earthquake among the traditional elites because new and populist-oriented parties have won. Yes, many legitimately wonder and worry what the result of the Trump presidency will be for US democracy and the world in general.

Still, we cannot be sure if this is just a brief setback for the expansion of democracy globally — that started in the early 1970s and was termed “the third wave of democracy” — or if it is simply the end of that wave, or if we have entered completely new and unknown territory.

A recent publication from the National Democratic Institute states that political parties in the 21st century face a number of existential challenges. Some of these are4:

» Why do disenfranchised citizens fail to see party activism as a mechanism to give voice to their concerns?

» How can parties with ideologies, platforms and programmes compete against the rise of populist or single-issue movements?

» If citizens feel disenfranchised with traditional parties, how can the parties then raise legitimate resources for their operations?

» How can political parties manage communication and outreach to keep up with changing citizen expectations?

» Can political parties find ways to reflect a commitment to women’s empowerment through policy goals and organisational culture?

I agree that these are valid and relevant issues to ponder, and political parties need to find convincing answers. The National Democratic Institute brought together a variety of political parties in 2017 to discuss solutions. The following recommendations could be useful for democratic parties anywhere in the world:5

» Lead by example: Political parties should develop truly democratic internal structures and practices if they wish to gain the trust of an increasingly informed and knowledgeable population.

» Think creatively about “ideology”: Unless ‘“ideology’” is translated into specific policy choices, it will remain an abstract notion and seen as meaningless by voters.

» Acknowledge citizens’ concerns: Many citizens feel that parties are out of touch. Leaders must reconnect with citizens and engage with them to find solutions to 21st century challenges.

» Prioritise gender equality: Women must have space to exercise their voice and agency, and mechanisms for zero tolerance of harassment and discrimination must be established.

» Transparency and accountability: Parties must be clear and honest about who their donors are, and how donations and public funds are spent.

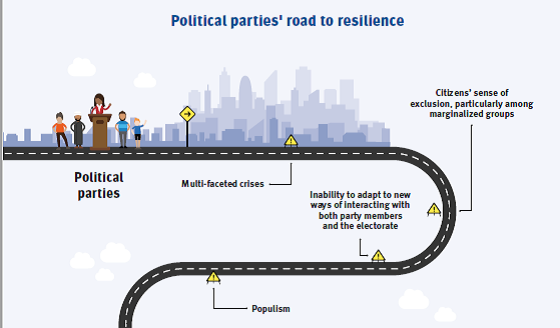

This approach is similar to the analysis made by International IDEA in a new publication about the global state of democracy. First, parties must deliver results to address multifaceted challenges such as global economic crises, international terrorism, and refugee flows. Second, parties must restore citizens’ sense of inclusion, particularly among marginalised groups. Third, traditional parties must find ways to respond to populism. Finally, parties need to adapt to new ways of interacting with both party members and the electorate.6

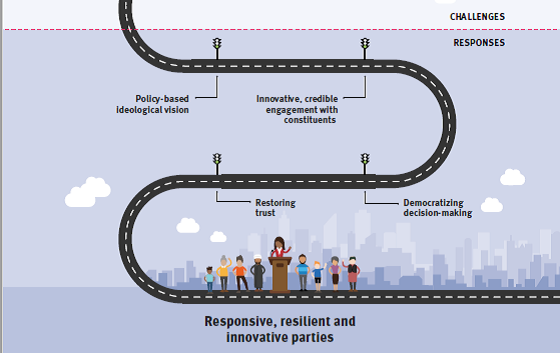

I agree with the challenges identified, and I agree that new policy visions, innovative engagement, democratic decision-making and efforts to restore trust are important areas to address, as illustrated in the report.

The recommendations from International IDEA are in line with those from the National Democratic Institute. Those mentioned below are only those that I feel add nuances and perspectives that might be inspiring for the relatively new parties now operating in Bhutan:7

» Communicate a strong political vision and offer fresh and innovative programmes to address current issues.

» Create alternative forms of citizen engagement through alternative forms of membership, like associate members or supporters.

» Carefully consider the use of direct democracy instruments such as referendums, being clear about the authority devolved to citizens, and the authority that remains with politicians.

» Remain responsive to the electorate between elections by rethinking communication strategies, updating internal cultures to match the increase in online and street-based interactions.

» Expand citizen engagement at all levels by using digital tools such as interactive websites and apps. This includes reaching out to members and non-members for help.

» Increase the transparency of information about elected representatives, including access to financial data about political campaigns and parties and financial interests of representatives.

Is There a Future for Political Parties?

We have become used to political parties being very different in different parts of the world. In Europe, the different parties grew out of the struggle between social classes, some taking a socialist ideology, others a conservative or a liberal ideology. Over time, new parties broke away from the first-generation parties, often positioning the new parties with a more mixed ideological platform, or with new versions of socialism, conservatism or liberalism.

Parties in Europe inspired political parties emerging in Latin America in the 19th century and in Africa and Asia in the 20th century. Naturally, history and culture gave the parties a local colour. A social democratic party in Denmark

could therefore be very different from its sisters in Nepal or Ghana. What is striking is that in virtually all liberal democracies developed around the world over 150 years, political parties have been the key instrument to deliver visions and policies. Despite the present crisis, I believe that this will be the case in the future as well.

My major concern is that the challenge or crisis goes deeper than what minor adjustments to the instruments required to fulfil the democratic functions are able to deliver. We experience a fundamental shift in thinking, and the

political parties and their leaders are to some extent themselves responsible for the “mess” we are in.

For too long, politicians have presented globalisation as a positive phenomenon only. Trade and investments with fewer and fewer restrictions would create wealth for all of us, rich and poor. Today it is clear that sentiments of antiglobalisation fuel much of the “populist” energy that created panic and upsets in elections and referendums in Europe and the US in recent years.

In addition, humanity is confronted with the challenges of climate change, tax evasion by the rich and the global companies through tax shelters, rapidly increasing inequality of wealth, uncontrollable flows of refugees from civil wars and failed states and international terrorism, just to mention some examples.

No wonder that people are concerned and confused. No wonder that political parties and party leaders are concerned and confused as well. No wonder that all of us have difficulty seeing through the haze of fake news and social media communication pointing in all directions. Some of the developments we have considered positive in the area of communication may not be helpful for our democracies after all. At the very least, they make it more difficult than it used to be to manage a political party and to show the leadership required.

One conclusion must be that the environment in which parties and leaders operate has become more difficult and demanding. This means that the parties on one hand must revisit the basics of how a political party functions democratically, and on the other hand, the new environment demands out-of-the-box thinking and strong leadership of a calibre we rarely see these days. It also requires a willingness to collaborate across the spectrum of parties and ideologies.

Finally, citizens need to rethink and reposition themselves as well. Our belief that parties and their leaders can deliver solutions to all of the many challenges facing the nation state in a globalised world is not realistic; just like the solutions presented by the populist parties are not at all realistic, but purely ideological.

References

1 “The Global State of Democracy 2017. Exploring Democracy’s Resilience.” International IDEA, 2017, page 102. The presentation uses information from the World Values Survey Waves 1-6, 1994-2014.2 “The Global State of Democracy 2017. Exploring Democracy’s Resilience.” International IDEA, 2017, page 109. The presentation uses information from the World Values Survey Waves 1-6, 1994-2014.

3 This framework is primarily based on writings by Pippa Norris, the Paul F. McGuire Lecturer in Comparative Politics at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. She is ranked the fourth most cited political scientist worldwide.

4 Reflect, Reform, Reengage: A Blueprint for 21st Century Parties. The National Democratic Institute, 2017. Page 9-10.

5 The recommendations are presented in the publication: “Reflect, Reform, Reengage: A Blueprint for 21st Century Parties”. The National Democratic Institute, 2017. Page 7-8. I have shortened and/or rephrased some of the recommendations.

6 “The Global State of Democracy 2017. Exploring Democracy’s Resilience.” International IDEA, 2017, page 101. The presentation uses information from the World Values Survey Waves 1-6, 1994-2014.

7 “The Global State of Democracy 2017. Exploring Democracy’s Resilience.” International IDEA, 2017, page 117-118. The presentation uses information from the World Values Survey Waves 1-6, 1994-2014. I have taken the liberty to shorten the text.