Socio-economic Status and Electoral Participation in Bhutan

Bhutan transitioned to a Democratic Constitutional Monarchy in 2008 and conducted its first parliamentary elections. In the words of former Chief Justice of Bhutan, Sonam Tobgye, the chairman of the then Constitution Drafting Committee, ‘Democracy in Bhutan is truly a result of the desire, aspiration and complete commitment of the monarchy to the well-being of the people and the country.’(Gallenkamp 2010). Since 1907, successive kings have planned the path of democratisation through modernisation and development, underpinned by Bhutan’s unique socio-economic, cultural and political settings. His Majesty The Fourth Druk Gyalpo proclaimed that ‘I do not believe that the system of absolute monarchy, wholly dependent on one individual, is a good system for the people in the long-run. Eventually, no matter how carefully royal children are prepared for their role, the country is bound to face misfortune of inheriting a King of dubious character.’ ( Sinpeng 2007).

As an important step towards democratisation, decentralisation of planning, devolved decision-making, and local development were initiated to provide first-hand experience in devolved local governance and development. These measures ensured that people could effectively participate in decisionmaking with the right to voice their hopes, aspirations and concerns in governance and development. The decentralisation of authority and responsibility was initiated in 1981 with the introduction of the Dzongkhag Yargye Tshogdu (District Council), responsible for development planning at the district level. With further decentralisation in 1991 to the gewog (county level), decision making and participation reached the grassroots level. This process of decentralisation provided the people to express their views and participate directly or indirectly in the decision making process. A gradual transition to decentralisation, participatory planning and grass root engagement has ultimately prepared the Bhutanese people to assume bigger roles in governance. In 1998, as a major step toward democratisation, a new Council of Ministers was elected by the members of the erstwhile National Assembly and were given all executive powers that were previously

the prerogatives of the Kings.

In 2001, through a Royal Decree, the drafting of the Constitution was commanded with the aim to ensure the sovereignty and security of Bhutan as a nation-state and to pave a future for Bhutan that is collectively decided and trodden. The need for a Constitution as per the Royal Decree was to establish a dynamic system of governance which would uphold the true principles of democracy and by which the collective will of the people of Bhutan will prevail in governance and in pursuit of development. The Constitution of Bhutan is the Supreme Law of the State and states that Bhutan shall become a Democratic Constitutional Monarchy, with elected government and parliament running the day-to-day affairs of governance and enacting laws. Thus, in preparation for Bhutan to become a democracy, the constitutional office of the Election Commission of Bhutan was established to oversee the preparation, maintenance, supervision, direction, control, and conduct of democratic elections, besides the establishment of the other offices of the constitutional post-holders.

It might be pointed here that, starting from 2002 onwards, the Gewog representatives were elected through secret ballots cast by voters over the age of 21 years and older, which truly entrenched in the Bhutanese people the concept of elections and voting.

In 2008, Bhutan became the then world’s youngest democracy having completed the conduct of the first ever parliamentary elections which saw a high voter turnout of 79.45 percent in a non-compulsory electoral system. In spite of the progressive and improved social and economic conditions of the Bhutanese people under the benevolent rule of successive monarchs, democratisation was neither the result of an impulsive desire nor a compulsive process of political change.

As Bhutan embarks on its third general elections in 2018, the whole world has its eyes on Bhutan, keenly observing the nascent democracy blossom to its right conditions. However, if the last general elections are any indication, there is higher voter apathy among Bhutanese voters and a decline in the voter participation could cost our democracy fortunes. So, what is next? Can Bhutanese be complacent and not bother about this important political process and participation? What are some of the impending parameters that deter electoral participation in Bhutan? The successive democratic governments have availed its opportunity to serve the people with best of ability within a limited resource. While political discourse remains superficial and politics primarily personal, every individual has the constitutional duty to cast their adult franchise and make responsible decision to elect the “best party” of their choice.

Globally, the low rate of electoral participation is linked to socio-economic factors such as income level, education level and political affinity. Bhutan is no different on this front and a study thereof has been undertaken to identify factors that affect electoral participation in Bhutan. Based on the Election Commission of Bhutan’s survey data on ‘the study of the determinants of voter’s choice and women’s participation in elective offices, 2014’, the socioeconomic status has been identified as being a strong predictor of electoral participation. The findings from this study is expected to provide the relevant agencies in addressing the issues that would help increase the voter turnout in 2018 general elections.

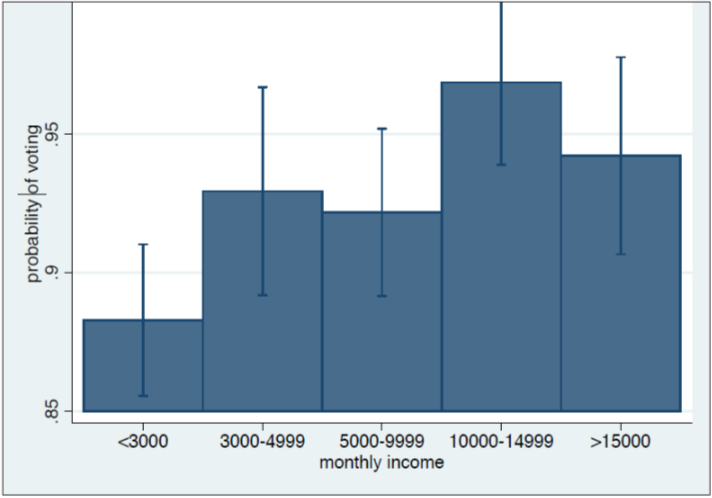

Income

According to several studies, income—that determines social status and economic prosperity—plays an important role in understanding voter participation (Brady et al. 1995; Lassen 2005; Wolfinger and Rosenstone 1980). Theory suggests that poor and marginalised voters are less likely to vote (Brady et al. 1995; Lijphart 1999). This is due to associated costs involved in the participation process. Also, higher levels of economic status and development, translated through higher income, have a positive relation in understanding the importance and consequences of voting that encourage greater participation.

Some believe that even in relatively equal societies, richer people are more likely to participate in politics than those with lesser economic resources. Higher income individuals are more likely to have larger networks, and they are more likely to talk about politics more frequently within their networks (Lake and Huckfeldt 1998).

Income is a strong predictor of electoral participation in Bhutan. Wealthier people, on average, are found to be more likely to vote than poorer people. This is consistent with findings of earlier studies in developed countries. The income variable used in the econometric model was categorised into five groups with less than Nu. 3,000 as poorest and a baseline for comparison. The estimation results indicate that people whose income is higher than the poorest group are more likely to participate.

Figure 1: Predicted probability of voting and income levels

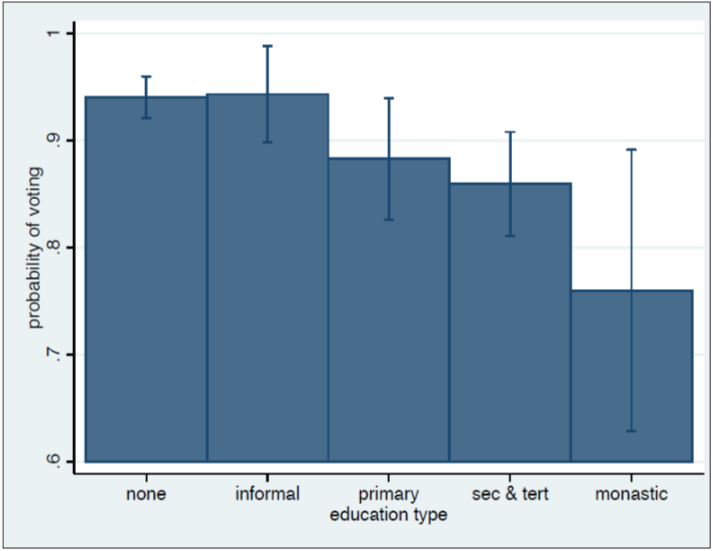

Education

Lake and Huckfeldt (1998) argue that education has a positive correlation to participation. The higher levels of education are also associated with reducing the cost of participation that provides incentives to engage in the electoral process. A qualified citizen is in a better position in terms of skills and knowledge to understand the complexity of the political system and assimilate information for effective participation. However, education produces different outcomes for developing countries and the recent studies suggest that an increase in the level of education does not necessarily increase electoral participation (Kolstad and Wiig 2016).

Education, despite being a strong predictor of voting, has produced different results in Bhutan. In contrast to the general findings that better educated people are more likely to participate, education in Bhutan is negatively correlated with electoral participation. It is found that with an increase in the level of education, people are less likely to participate in voting. The informal education groups are seen to vote slightly higher than the no education group as per Figure 2, but the difference is not statistically significant. My field experience, as an electoral officer for the last 10 years, suggests that this result is consistent with practical reality in Bhutan for several reasons.

Firstly, Bhutan follows an electoral registration system based on a civil registry rather than based on residency and accordingly voters can only vote from and in the places of their civil registry. This has a significant impact on people who work outside of their places of civil registry and these people are usually educated, working in cities and towns. These educated people are most unlikely to travel back to their villages to cast votes, either due to the distance or the associated cost of voting.

And secondly, the educated working people, in particular public servants, are barred from having affiliations to political parties since public servants cannot have political mandates and affiliations as per the existing laws. This is seen as a major deterrent for active participation among the educated group.

Figure 2: Predicted probability of voting and levels of education

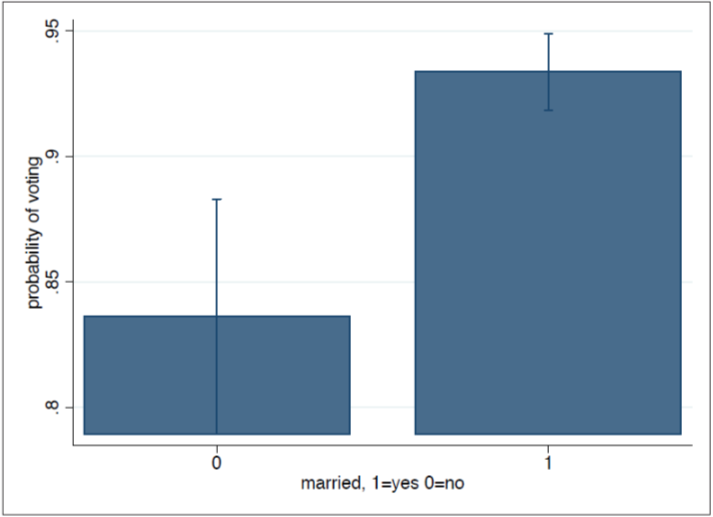

Marital status

Marital status has often been found to have a major influence on political decisions, including electoral participation and political support in the family. Some studies indicate that electoral participation is highest among young adults but decreases with marriage and drops significantly with children in the family (Wilensky 2002). However, others believe that separated and widowed people are less likely to vote than married and unmarried people as they lack companions to provide motivation for civic participation, or stressful process of ending a marriage (Wolfinger and Rosenstone 1980).

As some analysts of voter turnout compare married individuals to everyone else, data categories other than married and not married are combined in the model. The estimated results show that the predicted probability of voting is 0.94 for people who are married and 0.84 otherwise. This implies that married people are more likely to vote than those who are single, divorced or widowed. The international evidence suggests that this is because there is a strong influence of spouses on one another to vote and also support in sharing information related to participation (Wolfinger and Rosenstone 1980). Bhutan largely shares the same order of social bonding as other parts of the world in terms of family structure and married people are generally more responsible in their behaviour and actions towards political activities, including electoral participation. Further, people in Bhutan are assumed to take additional ownership and responsibility of governance by way of active engagement in choosing their representatives when there are children in the family.

Figure 5: Predicted probability of voting and marital status

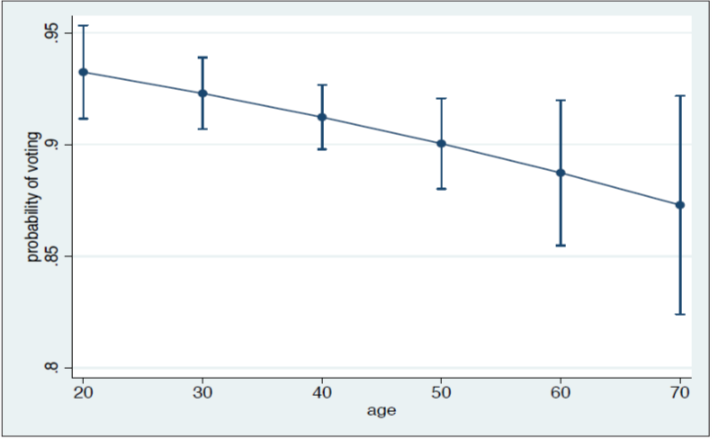

Age

Conventionally, age has not been a strong predictor of voting. The participation rate among different age groups are believed to be stereotypes with younger voters more liberal than older ones and evidence of a generation gap is significant with old voters more likely to vote than the young (Fisher 2008). However, when people reach 75 years and older, they are less likely to vote simply due to waning physical strength, movement and energy level (Strate et al. 1989).

Age, even though it is not a strong predictor of voting, when other variables (income, education, marital status, gender, religion, and tradition) are controlled for, a statistically significant relationship was found between age and electoral participation, with younger groups more likely to participate in voting than their older generation.

It is interesting to note, however, that the bivariate (two variables) relationship between age and voting produces opposite results. This indicates that when other factors are not taken into account, older people are more likely to vote than younger people. This observation is interesting and it can be assumed that their decision to vote is influenced by many variables beside age. Family obligation, social responsibilities, religious commitments are some possible factors that have influenced older people’s decision to vote in Bhutan.

Figure 3: Predicted probability of voting and age groups

Gender

The International IDEA’s data on voter turnout by gender and country shows no clear evidence that either men or women vote more. Data of voter turnout from 1945 to 1972 in Finland shows that the turnout of men is more than women consistently, while Malta recorded a higher number of women participating in parliamentary elections from 1976 to 2003 (International IDEA 2016). This indicates that the relationship between voter participation and gender is historically aligned to specific countries and not clearly on gender voting behavior.

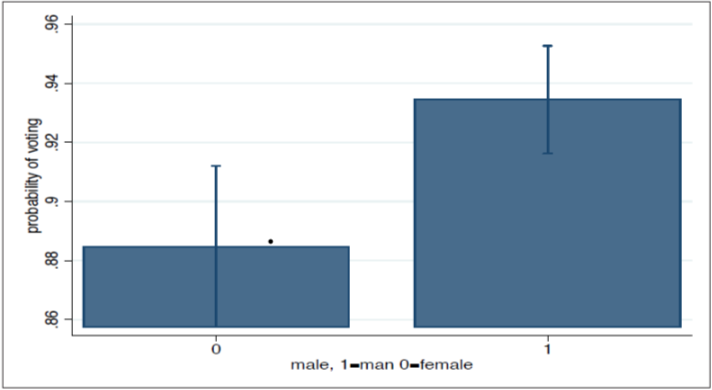

In Bhutan, however, the study indicates that men are more likely to vote than women. The regression (data) analysis suggest that, when more control variables are added to the model, the probability of voting increases for men compared to women which is supported by statistical significance. Several factors could account for these statistical findings:

- Men are more mobile and accessible to polling stations in rugged geographical conditions.

- The head of the family is always the man unless there is no male member in the family. Most of the time, family decisions are taken by the head of the family.

- Historically, men are politically active and represent in the public offices.

Figure 4: Predicted probability of voting and gender

Religion and Tradition

There has been no correlation established between religion and tradition and voting in Bhutan. Due to strong beliefs and devotion to religious beliefs and practices among the Bhutanese people, it might sound surprising not to have any relation between the religious beliefs and the decision to vote. One potential reason for the lack of correlation between these variables is due to the Constitutional requirement of clear separation of religious institutions and political institutions. According to a provision in the Electoral Act, all persons who are registered as religious personalities are considered above politics and they are not required to participate in the electoral process. The law also does not allow the formation of political parties based on religion, race, caste, or region.

Campaign and Electoral Information

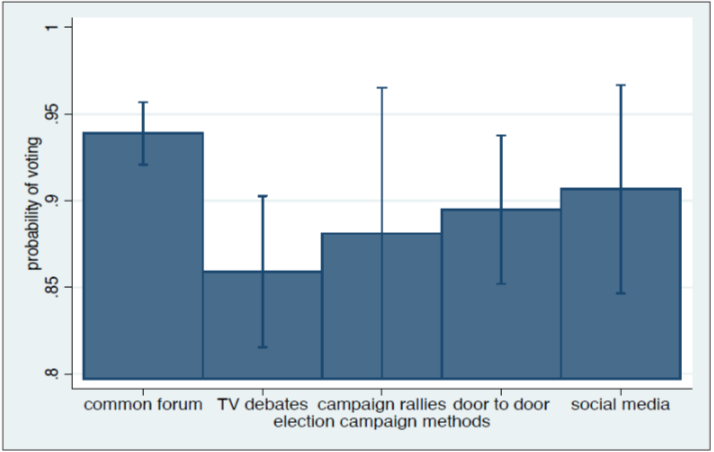

Political campaigns and electoral information are an integral part of a democratic process. Based on the levels of technological development and access to different forms of information and communication channels, political parties work with different strategies to win and garner votes within the rules of the game. Under the direction and control of the Election Commission of Bhutan (ECB), political parties in Bhutan can conduct election campaigns in the form of common forums, television debates, campaign rallies, doorto-door campaigns, and social media interactions. To ensure a level playing field amongst the political parties, the ECB regulates and monitors the use of uniform campaign materials–banners, posters, pamphlets, and placards for distribution—sponsored by the State as well as the parties themselves. All campaign platforms benefit people in getting timely information and knowledge. The findings of this study, in which information was measured with common forums as the base category, show that people are less likely to vote if they primarily participate in the campaign through other forms of campaigns relative to common forums. In other words, the statistical evidence indicates that people are more likely to vote if they have attended common forums.

The simple assumption of this outcome can be attributed to access and coverage of the campaign information. Common forums are organised and coordinated by the ECB in all the communities and villages for all political parties and the political parties are required to address the forums mandatorily. The idea of all political parties addressing the common forums at the same time moderated by the electoral authority ensures that there is a level playing field for parties to communicate their campaign promises without necessarily resorting to negative campaigning. As voters can attend electoral campaigns for all parties together in the common forums, this has become a popular campaign strategy.

While other forms of campaigns are practiced by political parties, these have received mixed reactions to their approach and effectiveness. Door-to-door campaigns for example have been criticised for being susceptible to corruption and bribery. The post election review reports indicate that voters do not accrue any additional benefit from door-to-door campaigns, rather they create social discord and community divisions, and the reports suggest that be done away with.

Even though the television debates and the information dissemination undertaken through social media are very effective communication channels, only a handful of voters have access to such modern technology driven information dissemination.

Figure 6: Probability of voting influenced by electoral campaign strategies

Other Control Variables

Party discord has been included as one variable in the model, as there have been many instances of party coordinators and workers influencing and creating communal discords during elections.

However, the results indicate that there is no correlation between individuals’ concerns with party discords and electoral participation.

The residence of the voter was included in the model to see if either urban or rural people are more likely to vote. The regression results show that there is no difference between the voters residing in urban and rural in terms of electoral participation.

Electoral promises are an important party policy that translates into government policies for the party in power. After the first elections, there were instances where the political parties and their candidates made campaign promises which were beyond their mandates, and this has been a concern for the electorates. The positive relationship between voting and the concern of unrealistic promises being made at elections suggests that the problem with unrealistic promises is not one of the main reasons people are not voting. However, the finding does also suggest that unrealistic promises are a concern for people who are choosing to take part in the electoral process.

Conclusion

This study investigated the impact of socio-economic status on the electoral participation. Using survey data, the analysis involved a logistic regression (Logistic regression is a statistical method for analyzing a dataset in which there are one or more independent variables that determine an outcome). The results indicate that controlling for other control variables that are relevant to the decision of individual voters in Bhutan, people with higher incomes are more likely to vote than people with less income. This finding of lower turnout of poor people in Bhutan can be associated with the cost of voting and access to information on elections. Further, this study indicates that men are more likely to vote than women, the married people are more likely to vote than the single, divorced or widowed people, and the common forums appear to be the method of electoral campaigning most likely to motivate people to vote.

Contrary to previous studies of positive correlation between education and electoral participation, education in Bhutan is found to have a negative correlation to electoral participation, which indicates that with an increase in the level of education, people are less likely to vote. This finding in Bhutan, however, can be related to the provisions in electoral laws that stipulate the system of voter registration, which is based on the civil registry. This finding also can be attributed to constitutional provisions of apolitical mandate of public servants that distance educated public servants from politics and political activities.

The impact of socio-economic status on electoral participation could have substantial consequences for the Bhutanese political institutions and democracy. The findings from this study suggest that there is an opportunity for policy reform to design programme that could help in reducing the impact of socio-economic status in the electoral participation in Bhutan.

First, poor people are less likely to vote because of the cost associated with voting and due to lack of information on the importance of voting and access to campaign information. This problem can be addressed by making electoral education and voter information more accessible to poor people and placing polling stations near to them. Special programmes can be designed targeting poor people and remote voters to encourage their future participation.

Second, voters frequently attend common forums and extending this coordinated campaign method can help voters access information on political parties and candidates. The common forums may be taken beyond the present locations of gewogs (local government) and thromdes (municipal). The common forums at every chiwogs (group of communities) level might encourage people to access information and motivate to vote in the future elections.

Third, there is a large difference between voter participation of married people with that of others—single, widowed, and divorced. To understand this demographic representation of voting population, a separate study on this might help in targeting these groups.

Fourth, education being negatively correlated to electoral participation may have substantial consequences for the sustainability of electoral democracy in Bhutan. Additional effort must be made both by the election authority and the political parties to engage educated voters to participate in future elections.

Fifth, exploring alternatives for people who live in the cities by allowing them to vote in the cities might help increase the educated voters to vote in future elections.

This study is the first of a kind in Bhutan to investigate the affect of socio-economic status on electoral participation and the paper hopes to facilitate policy debates and discussions aimed at increasing participation in Bhutan’s future elections.

This survey data is drawn from the national population, surveyed based on random sampling, with a sample size of 1,546. While the data is weighted to generate estimates that are nationally representative, it is not without limitations. The voter turnout from the survey data indicates 90 percent while the actual voter turnout was only 66.13 percent (2013) which could be due to social desirability bias (response bias like over reporting or under reporting of the facts) in the survey data. This study then leaves ample opportunity for future researches, covering broad areas of democracy and elections in Bhutan.

For references visit www.drukjournal.bt