The cultural construction of Bhutan: an unfinished story

You can download this Article as a PDF by clicking here

Our future sovereignty as a nation-state will continue to depend upon the articulation of a cultural imperative that asserts our distinctive Bhutanese identity.*

Most Bhutanese would be familiar with the postulation that Bhutan’s survival as an independent nation rests on its unique cultural identity. That, in the absence of military might or economic power, Bhutan’s sovereignty hinges on its unique cultural heritage, which makes Bhutan distinct among other nations in the frenzy of a globalised meld. Culture is seen as the binding force, which unites the Bhutanese and, as one of the pillars of Gross National Happiness, it is regarded as Bhutan’s shield against the negative and disrupting influences of modernisation and globalisation.

Yet, very few people ask what really constitutes the Bhutanese cultural identity. Even fewer delve into the issues of cultural construction to unravel the assumptions and articulate Bhutan’s cultural identity. Beyond the affiliation to the state through citizenship, what shared values, social practices and cultural features unite the Bhutanese as a homogenous cultural group? What common features help forge a shared Bhutanese cultural identity, if there is such a thing? What intrinsic characteristics bind the diverse expressions in the Bhutanese cultural realms as a cognate, and yet distinct from the cultures of neighbouring states of Northern India, Nepal and Tibet?

Granted that one adequately understands these cultural values and practices, a more exigent question for Bhutan’s cultural discourse is whether or not enough is being done to safeguard and reinforce Bhutan’s cultural and linguistic heritage in the face of widespread global influence. What will Bhutan be like and how will the Bhutanese think, feel, speak, dress and relate after 50 years at the current pace of change? What kind of Bhutan can one envisage half a century from now in terms of cultural identity, and is Bhutan heading in that direction? If the specific cases of personal, communal and national beliefs and practices change beyond recognition, what is the essential Bhutanese-ness, which could maintain Bhutan’s cultural distinctiveness? Consequently, is Bhutan’s sovereignty, which purportedly depends on its cultural uniqueness, being compromised with the rapid cultural changes occurring in the country?

While on the one hand, there are such questions to be raised regarding cultural distinction, there is also, on the other, the broader question of how viable and progressive an argument for cultural unity is in an era where multiculturalism is the dominant discourse around the world. In spite of the serious problems, such as religious fundamentalism, arising out of cultural differences, nations are bent on cultural plurality and inclusivism. In the aftermath of the recent massacre at the premises of the French satirical magazine Charle Hebdo due to cultural parochialism, global leaders united to call for multiculturalism and ecumenism and defend even the faith in the name of which the massacre was perpetrated. Where does Bhutan’s emphasis on cultural identity for sovereignty stand in the context of such global developments of multiculturalism and innovation? There are many such questions essential to the cultural construction of a nation-state, which call for deeper reflection and discussions.

Unity in cultural diversity

The first challenge for the postulation of Bhutan’s cultural distinctness is the lack of adequate knowledge of Bhutan’s cultural heritage. After decades of reiterating the importance of culture, there is still no substantive inventory, let alone an in-depth understanding, of Bhutan’s tangible and intangible cultural heritage. A workshop organised in 2013 by Shejun, a private agency for cultural documentation, bringing together over two dozen cultural experts, revealed that Bhutan’s cultural landscape is largely uncharted. After two days, the workshop produced a list of over 1,000 cultural categories such as tshechu, lomba, kharphu, puta-making, ink-making, blood-letting, tongue twisters, etc.- to give a few examples. The list is far from comprehensive and complete and details about the origin, significance, procedures, and functions of these traditional cultures are mostly unknown except by the few local practitioners. Our knowledge of Bhutan’s diverse cultures remains dispersed and fragmented, held mainly by the cultural virtuosi in the particular localities.

There is neither an effective nodal repository or a custodial agency with the clear mandate to look after Bhutan’s cultural heritage, nor attempts at an integrated study to understand its significance as a whole. The state budget for the culture sector, including the development of the national language, hovered around 3% of the national budget for the last few decades. With lukewarm support from the state, efforts to take stock of and study Bhutan’s cultures were inadequate to say the least. The few projects initiated by different organisations and agencies to fill this gap lacked proper co-ordination and scale to have the desirable impact. In the meantime, the traditional elders in the specific localities, who are the main practitioners of the traditional cultures, are now a very small minority and their numbers are diminishing each day

In the absence of comprehensive knowledge and information about Bhutan’s various traditional cultures, there has been a tendency to overlook diversity and treat these cultures as homogeneous. In the final decades of the 20th century, even the state offices responsible for preserving Bhutan’s cultures initiated, ironically and perhaps unwittingly, projects of standardisation in order to eliminate variations and promote uniformity. This proclivity for uniformity and monoculturalism was partly also provoked by the nationalistic sentiments which were on the rise due to the perceived demographic threat and dissidence from the southern districts. Using concepts such as “one nation, one people”, the approach in demand then was one of unity through cultural integration rather than inclusion. Appreciation of cultural diversity was not a national imperative.

The inclination for cultural uniformity and low appreciation of diversity also roughly coincided with the rise of some new pan-Bhutanese cultural features as a result of the migration and mingling of the people. With better communication facilities such a roads, which increased people’s mobility, and new social avenues such as schools and workplaces, which brought people together, Bhutan saw an unprecedented intermingling of its people and fusion of its cultures. Just as the nation found a new lingua franca in Dzongkha and English, it saw the development of shared cultural experiences such as ema datshi and sweet milk tea as a pan-Bhutanese cuisine.

Against this trend of cultural fusion, which is further aggravated by the forces of globalisation, a new awareness of cultural diversity is emerging. People are beginning to appreciate the localised specificities and variations as much as enjoying the shared cultural experiences. In a recent brainstorming session to draft the first Intangible Cultural Heritage Bill for the country, the expert participants agreed to classify Bhutan’s intangible cultures into two categories of those with nationwide and local significance and presence and to rank them fairly for their uniqueness and endangerment. Some participants reiterated the need to respect local particulars such as local dance or song and to safeguard them from being replaced by the dominant cultures promoted as national norms by the state organs such as government offices and the Royal Academy of Performing Arts.

Both international discourses of multiculturalism and local developments of cultural conscientiousness today signal a new direction for Bhutan’s conversations on culture. The situation augurs well for a new approach to speak about Bhutan’s “cultures” and not a singular ‘culture’, and about the rich cultural and linguistic diversity generated by Bhutan’s geographic segregation and isolation, as a national asset and strength in the midst of a world which is increasingly becoming mixed and monotonous. It calls for policies and strategies to craft a Bhutanese cultural identity based on cultural plurality, which can be enthusiastically shared by all Bhutanese using the advantages of modern facilities and technology.

The paradox of cultural change

The perception of culture in Bhutan is preponderantly one of its connection to the past and Bhutan’s long held traditions rather than that of cultural dynamism and innovation so much so that change is seen as inimical to culture. Given the wholesome and progressive nature of Bhutan’s pre-Buddhist and Buddhist cultural traditions, the official discourse on culture in Bhutan mainly dwells on its preservation and promotion. It is mainly through sustaining its traditional cultures that Bhutan seeks to balance material development with spiritual wellbeing, and modernity with tradition. Thus, culture lies at the heart of Bhutan’s holistic GNH approach to human progress and Bhutan has become well known as a country that is very serious about its traditional cultures.

Yet, in spite of the rhetoric of cultural preservation and Bhutan’s reputation as a bastion of its traditional cultures, Bhutan’s cultural landscape is changing at an unprecedented pace. One can safely claim that Bhutan has undergone much more change in the last 50 years than it had in the 500 years before that. Due to the successful programmes of modernisation and the widespread influence of the outside world through education, tourism, travel and media, Bhutan is witnessing the adaptation, alteration, decline and disappearance of traditional cultures at a scale and rate never seen in the past. In some cases, one can even witness the invention of cultures for nationalistic or other purposes.

The entire Bhutanese worldview, with its value systems, ideas, behaviours and socio-cultural life conditions, is in a drastic transition. Traditional animistic and Buddhist belief systems are now being replaced by modern scientific knowledge, local values and practices by national and global values and trends, vernacular languages by English, subsistence farming by the consumerist capitalism, and village communities by urban settlements. If traditional cultures are what Bhutan hopes to be the bulwarks against unwanted outside influences, these bulwarks are now eroding as the older generation, which is the custodian of these cultures, is dying and most of the youth remain enamoured of the modern materialistic culture flowing in from outside.

The change is quite palpable today on the streets of Thimphu, both in the form of tangible objects and behavioural patterns. Nonetheless, most Bhutanese, including the state, appear to remain oblivious to the gradual process of acculturation and suffer from a boiling frog syndrome. Let’s take the case of the national dress culture as an example of such insidious change. Most Bhutanese men today do not wear gho outside of the official work place and hours. The culture of wearing gho, one can argue easily, has diminished to such an extent that only a minority of men wear it most of their time. If this trend continues and a person increasingly wears trousers more than gho, when does the person stop being Bhutanese in terms of dress culture and join the global amalgam? Would wearing a gho once a month, for instance, suffice for someone to be considered a Bhutanese in his dress culture? When does someone stop being a Bhutanese and begin becoming a non-Bhutanese with regard to dress culture? There is nothing wrong in Bhutan joining the global dress culture, but is that the preferred choice?

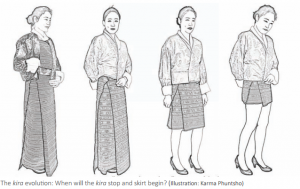

Kira, the traditional dress of the Bhutanese women, has been lamentably halved in the last few decades. Today, proper full kira has become a very rare commodity even in the shops and the term kira has become synonymous with half-kira, which resembles an Indian lungi or a Thai sarong in size. Just as the top half of kira has been truncated, what would it be like if the bottom quarter is curtailed? Would it be a kira or a skirt? When will it stop being a kira and its essence of being a Bhutanese costume cease? Where do we draw the line? The same question can be asked about other markers of Bhutanese cultural identity including ideas, language, food, music, art, etc. If Bhutanese people do not hold the Bhutanese belief systems, carry on the traditional values, speak the local languages, play traditional music or eat local cuisine, what would distinguish them as culturally Bhutanese?

There is no denying that culture, like other conditioned things, is impermanent and subject to change and evolution. It is important to appreciate cultural dynamism and not be hostile towards adaptation and modification of traditional cultures in order to suit the prevalent aesthetic or utilitarian values and needs. With rapid improvements in technology and lifestyle, cultures around the world are in their most fluid and fleeting state today, and Bhutan is no exception. It would neither be advisable nor feasible to insist on using traditional plough and yoke, for instance, when there are more effective technologies available to till the land. Nonetheless, Bhutan’s real challenge lies in finding a fine balance and ushering a meaningful change so that, for a country that prides itself on cultural preservation, the essential fabric of cultural identity is not entirely lost

There is no denying that culture, like other conditioned things, is impermanent and subject to change and evolution. It is important to appreciate cultural dynamism and not be hostile towards adaptation and modification of traditional cultures in order to suit the prevalent aesthetic or utilitarian values and needs. With rapid improvements in technology and lifestyle, cultures around the world are in their most fluid and fleeting state today, and Bhutan is no exception. It would neither be advisable nor feasible to insist on using traditional plough and yoke, for instance, when there are more effective technologies available to till the land. Nonetheless, Bhutan’s real challenge lies in finding a fine balance and ushering a meaningful change so that, for a country that prides itself on cultural preservation, the essential fabric of cultural identity is not entirely lost

While seeking progressive change and innovation and rethinking about culture as a dynamic process, Bhutan must find a way to curb the flow of unwanted influence and steer cultural change towards the right direction. To begin with, it must do rigorous thinking on (i) what aspects of its cultures it wishes to sustain as status quo, (ii) what can be modified and adapted, and (iii) what may be gracefully relinquished. Clearly, some cultural artefacts and practices have already lost their value and utility and may be saved only as museum pieces for historical significance, while others can be sustained with minor modifications without losing their core values and functions. It is also critical to recognise which cultures constitute the core values and traditions of the Bhutanese nationhood and which can be dispensed with without serious consequences to the people’s wellbeing or national sovereignty.

Unfortunately, Bhutan remains as vague and unaware of these issues as most other nations in the world. Meanwhile, cultural transformation in Bhutan, like in the rest of the world, is often being driven by the capricious taste in vogue and the market forces. Considerable changes are sweeping across the country triggered by social trends and emerging economic and technological developments. The vast majority of the populace, caught in the frenzy of fast development, remains unaware of the insidious changes and their consequence or of the long-term national interests. In such a situation, should the course of cultural construction be left, in a democratic spirit, to the social trends and the taste and desires of the masses, or should the visionary leaders and the state intervene to provide a more proactive and firm direction? It is hugely improbable that Bhutan can dance to the tune of changing times and at the same time win the game of retaining its cultural integrity. It seems inevitable that if Bhutan wishes to take its policy of cultural preservation seriously, the decision for cultural formation cannot be left up to the popular choices and more robust cultural policies and programmes need to be in place to steer the process of change in a healthy direction.

The challenges of cultural construction

It is quite clear from the ongoing social trends and patterns that Bhutan faces serious challenges in securing its cultural traditions among the young citizens in the long run. For a start, Bhutan has to work on undoing the polarised perception of tradition/culture vis- à-vis modernity/change ± the predilection to see tradition as static and conservative and modernity as progressive and forward looking. Most young Bhutanese mistakenly associate traditional cultures with the past and also more directly with tangible objects, as they find it easier to recognise cultures with material forms and glamourous nature. However, mainly due to the impact of the exogenous educational system Bhutan adopted, cultural experts notice a sad oversight of the intangible cultures of ideas, values, principles, oral transmissions, social behaviours and events, which inform the tangible cultural expressions and help sustain the integrity of the individual, community and nation.

Cultural promoters feel that these oversights and misconceptions need to be effectively addressed. People need to be taught that cultures are not merely about the past and that they are as relevant to human wellbeing and prosperity in the present and future as they were in the past. Similarly, it has to be clearly communicated that cultures play an important role in human life experience and wellbeing. On an individual level, the cultural facets of a person form the bedrock of personal identity. The cultural traits and roles make up the social, epistemological and existential self of a person and these cultural components determine the quality of personal life experience. On the level of community, the cultural ideas and practices serve as the social cement to hold societies together. It is the shared values, mores and practices, which help the smooth running of a society and through which people design their shared environment and experiences

It is a fact that the benefits of cultures are not limited to the local area in current times. With profuse exchange and fusion through communication facilities, formerly isolated cultures have found universal relevance. More than half of the audience in some local festivals is tourists from abroad. Similarly, meditation and yoga ± cultural practices well known in the Bhutanese tradition ± are two good examples of cultures which have gained global appeal and penetrated even mainstream western societies. The applicability of cultures beyond former cultural borders is even greater in the case of perceptible cultures such as music, art and culinary recipes. Bhutan’s cultural practices such as textile production, architectural designs and healing practices have already received great attention from the people of other countries. It is primarily through understanding the significance and potential, which their cultures hold for themselves and the world, that the Bhutanese can be encouraged to cherish their cultural heritage.

The other main challenge that Bhutan seems to be facing is making its cultures attractive and affordable to its youth by drawing on their dynamic and versatile nature. The proliferation of the new brand of tshoglham boots with comfortable soles and the zhungdra performance at the popular Drukstar contest are good examples of how cultures can be positively adapted and made popular. Most cultures are feasible for adaptations without losing the core values; an intelligent rebranding can trigger enhanced attraction without any serious change. Tshejor’s Ezay, a Bhutanese homemade pickle brand, is today in demand even outside Bhutan. For a population group driven by fashion and peer pressure, a trick to promoting culture may lie in ingeniously creating a cultural fad by the leaders and elites to whom the masses and youth look up as role models. A creative re-presentation of cultures as fashionable and progressive by the top leaders, in the same way Bhutan has packaged happiness, could attract both the Bhutanese and foreign interests. This may gradually lead future citizens to learn to appreciate the cultures and benefit from their values, and not just foster a sentimental attachment to them for historical reasons

In the current global context, the survival of cultures is also tied to their economic expedience. While shunning unethical commercialization of cultural traditions, Bhutan’s cultures will have to become economically viable. In the past decades, Bhutan has seen an increasing number of people drop their traditional rituals or even convert to other faiths due to the economic burden some cultural practices entail. Although it is wrong to put cultural transactions in pure economic values using popular accounting methods, it is important that cultural experience, however costly, engender psychological, social or economic returns commensurate to the investments and costs. To this effect, various efforts are being made by the state and NGOs such as Helvetas, the Loden Foundation and Tarayana in leveraging the cultures to bring socioeconomic benefit to the practitioners so that the transmission of culture does not become an economic burden but is viewed as an opportunity. As people avidly seek prosperity, Bhutan will increasingly see the economisation of its cultures, and the marriage between economy and culture would determine their mutual sustainability and progress

Finally, if our understanding of cultural identity is a non-essentialist one based on the diversity of cultural factors, a genuine appreciation of cultural variety and difference is crucial in all endeavours to safeguard and promote cultures. This would be also in tune with the Buddhist idea of non-self or absence of self-existence beyond the numerous social, psychological and physical components and conditions which make up personal identity and also in tandem with contemporary theories of cultural identity as combination of various cultural identifiers. A single factor or an identifier such as citizenship, religious faith or political allegiance do not define the cultural identity of a Bhutanese person. As cultural identity is made up of the myriad small things in life including the beliefs, place, profession, community, family, dress, food, leisure activities, etc., Bhutan’s discourse on cultural identity must give due regard to these numerous components. What ultimately will define the Bhutanese identity if Bhutanese stop wearing the traditional dress, eating Bhutanese cuisine, speaking Bhutanese languages, reading and writing Bhutanese literature and observing traditional social events and customs? Will the state rituals and official routines and insignias promoted through state support be sufficient to forge the Bhutanese identity?

State visions and government policies are generally clear about the political and economic direction of Bhutan and the country has also achieved great progress. Bhutan claimed to have even surpassed most of the Millennium Development Goals before the deadline (Kuensel, 23/1/15) in terms of socio-economic development. However, Bhutan’s vision and strategies with regard to cultural identity remains generally vague and indecisive. It is not clear what first language Bhutan aims to have its citizens speak in 50 years’ time, which cultural traits it would keep to make Bhutan distinct from the rest of the world if it wishes to do so, and how it plans to deal with the deluge of cultural change it is witnessing today. For a country which hangs its entire sovereignty and future prospects on its cultural identity, there are many questions one must ask to address the naivety and ingenuousness about cultural construction. The questions are not timid and regressive ones of returning to the “roots” but bold and progressive ones about the future “route” which will truly embody Bhutan’s rich cultural blessings and the pursuit of Gross National Happiness on unique Bhutanese terms.

References

*Royal Government of Bhutan. Bhutan 2020, p.27. 1999