What is the “Bhutanese-ness” of the Bhutanese people?

You can download this Article as a PDF by clicking here

World leaders, anthropologists, philosophers, stateless people around the world have pondered over the question of national identity, trying to define and re-define it at different times, under different circumstances, in different perspectives. Many believe that it is not really definable. But the discourse goes on.

This paper grapples with the question, what is the “Bhutanese-ness” of the Bhutanese people? It looks at the Bhutanese image and identity shaped by a rugged geography and mythological history, the consistent emphasis on culture, the impact of Gross National Happiness (GNH), the survival instinct of a small country with a strong threat perception, and a system of governance that was taken over from realised Lamas by hereditary Kings who then conferred the responsibility on the people. It concludes that to truly achieve the big dreams of a small nation the contentment of the people – the Bhutanese people must develop a shared consciousness that means shared values as the essence of a national identity. This shared consciousness perceives the Druk Gyalpo, who is the Head of State, as the unifying factor who personifies Bhutan’s vision for the future.

Over the centuries the citizens of Palden Drukpa have manifested their identity in various forms: ngagoes admired for the size of their calves; women farmers who gave birth in the rice field and kept working; chest-thumping chimis and their eloquent rhetoric in the National Assembly; students patriotically inspired to eat an exaggerated amount of chillis when they are overseas; defensive citizens angered by even constructive criticism of Bhutan; proud officials in glittering ghos and kiras at international conferences. Now there are the young rap dancers with gho sleeves tied around the waist, rigsar pop stars, the archers, footballers, and cricketers representing Bhutan in the international arena, the academics sharing GNH around the world. And there have always been the yogis meditating in caves up in the mountains.

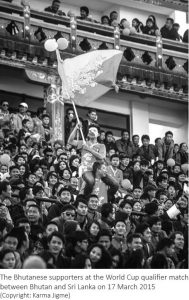

Image

Many Bhutanese, old and young, have at some stage basked in the romanticised images of The Last Shangrila, The Hidden Kingdom, Switzerland of the East, The Happiest Country. Many have, deliberately or inadvertently, acknowledged and even encouraged this perception among visitors, sometimes with uneasiness, knowing that things are not quite ideal. But this mystical image has worked for Bhutan which is now a declared global tourist hotspot.

Many Bhutanese, old and young, have at some stage basked in the romanticised images of The Last Shangrila, The Hidden Kingdom, Switzerland of the East, The Happiest Country. Many have, deliberately or inadvertently, acknowledged and even encouraged this perception among visitors, sometimes with uneasiness, knowing that things are not quite ideal. But this mystical image has worked for Bhutan which is now a declared global tourist hotspot.

The perception of being truly unique has been drummed into the Bhutanese citizen by parents, school teachers, politicians, and even by foreign visitors. Many a respected visitor has told Bhutanese friends: “You are so lucky you have your culture intact. We have lost ours.” This has been taken to such an extent that a resident foreigner was once known to have angrily retorted: “You Bhutanese keep telling us you are unique. Are you saying that the rest of us are common?”

Not long ago Bhutanese travellers had to face puzzled or suspicious immigration officials whenever they landed in another country. The Bhutanese passport was not recognised until immigration systems around the world were computerised. Today, however, there are very few people, from Thai taxi drivers to Silicon Valley magnates, who have not heard of Bhutan. Bhutanese citizens need not try to convince foreigners any longer that they are not Koreans or Japanese, not Nepalis or Indians.

Beyond symbols for survival

With an acute geo-political consciousness, Bhutanese leaders of the past made the famously pragmatic decision to survive by hiding in the folds of the Himalayas. It worked. Beneath the national language, national flag, national anthem, national flower, national animal, and so on, and deep within the national dress code as well as the laws governing art and architecture, lay a strong survival instinct. As the form of external threats metamorphosed from military aggression, media invasion, demographic evolution to globalisation and materialism, the Bhutanese leadership decided that Bhutan’s survival lay in the preservation of the Bhutanese identity. A population of a little more than half a million people living in a region that is home to two fifths of mankind not only had to be different but had to look different to survive. This threat perception of a small population with large neighbours helped define and preserve the Bhutanese cultural identity.

The debate continues today at a more existential level. The interest of the community has primacy over the rights of an individual. Individual rights, as often discussed in the West, is important, but not at the cost of the community or society. Therefore, the government’s insistence on the traditional dress code, traditional architecture being mandated by law, and the continued emphasis on traditional ceremonies is a localised response to globalisation. But it is also important to note that, despite the emphasis on the community, personal interests often render traditional practices as cosmetic rituals.

The need to separate “us” and “them” was prevalent since Tibet was perceived as a threat in the mid-eighteenth century. Bhutan refined the national dress code and social etiquette, reformed the theocratic system of governance, and adjusted the lunar calender to differentiate itself from Tibet. In the late 1980s and early 1990s Bhutanese leaders viewed the 16 million ethnic Nepali people in India, most of them living in the Duars belt along Bhutan’s southern border, as a potential demographic threat. This was aggravated by the Gorkhaland movement in Darjeeling where the Ghorka National Liberation Front wrested administrative autonomy from the West Bengal government in Kolkata in the mid 1980s. A less spoken but more stark reminder was the fact that the original Bhutia population in Sikkim was far outnumbered by the ethnic Nepalis when Sikkim became the 25th state of India.

In response to the spread of the Nepali population eastwards across the Himalayas, the government strengthened the implementation of its immigration and citizenship laws and reiterated the emphasis on Bhutan’s cultural identity. Families of the Nepali minority in Bhutan were affected, resulting in a disgruntled population in the south. This eventually led to an exodus of more than 50,000 ethnic Nepalis to UNHCR-sponsored camps in eastern Nepal, leading to what is known as the “refugee problem” today.

Emotions not enough

In defining national identity, it is not enough just to “feel” Bhutanese. Patriotism or nationalism, as emotions, are inadequate. Today, how many Bhutanese will die for Bhutan? Why or why not? But this is passion at its most extreme. It is more important to cultivate a reasoned definition of the Bhutanese identity drawn from a shared consciousness of the country’s history and geography, culture and traditions, politics and governance, values and priorities.

History and Geography

National identity is influenced by history and geography. Bhutanese history, chronicled in spiritual texts, reads like mythology. This is what gave Bhutan the mystical image that defined the country for decades. The Bhutanese identity evolved as the governance of society changed from the theocracy of the Zhabdrung in the 17th century, into a dual system, to an heriditary Monarchy in 1907, and then to a Democratic Constitutional Monarchy in 2008. The small rural communities grew into a society, and then a populace. Art and literature survived as an oral tradition among the rural communities but the preservation of culture was a top-down exercise. And while the history of the nation-building process can be a cruel one Bhutan was spared much of that pain. It remained unconquered, because of the caution adopted by the leadership and the good fortune of its geographic isolation. This has, in fact, become a source of pride to today’s generations.

The name, Bhutan, has geographic roots, stemming from Bhotanta which means “the end” of Bhot or Tibet. The British mapped the country as Bootan, Boutan, Bhotan and, after 1865, Bhutan.

It was because of Britain’s requirement to administer its colonies that the British mapped the region as we know it today. Boundaries were created as a part of dynastic expansion. Maps were used to indicate features that already existed. And it was thus that Bhutan’s boundaries were etched: “that boulder” was joined to “that ravine” which was joined to “that peak” and so on. In fact, Bhutan is still drawing the northern boundaries of its map today.

Culture

Centuries of isolation, a cautious growth policy since 1960, and an intuitive survival instinct enabled Bhutan to keep its cultural heritage largely intact. In their determination to preserve its cultural heritage the custodians of tradition interpreted culture as being synonymous with Buddhism from where the cultural identity had been drawn. But, despite legislation and regulations that were developed to maintian the status quo, rapid change over four decades had consequences. Bhutan was forced to grapple with new challenges that included an evolving culture.

Unique referred to the old and traditional even as the country embarked on a process of planned development and modernisation. The result was that the broader evolving aspects of culture, particularly the lifestyle and values of youth including the pop trends – were neglected. The narrow interpretation of culture excluded youth and some minorities in the national narrative. Many Bhutanese youngsters spend three or four nights a week in the discotheques which are derided as foreign culture. Hollywood and Bollywood had already come into the Bhutanese houses and a generation born in this period could not quite fathom the basis of their parents’ identity.

At the same time, the terminology most commonly connected with traditional culture lost their true meaning in this process. Historian and philosopher, Dr Karma Phuntsho, notes that the terminology used to convey a sense of Bhutanese cultural values have become meaningless rhetoric. Le judre, tha damtshig, driglam namzha are very frequently and profusely heard in Bhutan and are taken for granted without any knowledge of their significance. They are originally religious or para-religious concepts and they acquired, mostly in recent years, a secular and political dimension to their application.

Traditions and values must also evolve with the times. Bhutan’s cultural dream must turn into a reality that includes all citizens, especially its own youth. Culture must include the traditional beliefs, sentiments, and knowledge, as well as the languages and creeds we have inherited and the political and economic systems that are evolving. And it cannot avoid the lifestyle, fashions and fancies of the youth. This means that today’s leaders must adopt the appropriate and reject the inappropriate values that are being imported through increased exposure, “modern education”, and media explosion.

Shared national consciousness

Buddhism describes identity as being in the mind, or consciousness. In 1983 Benedict Anderson wrote Imagined Communities, an inspiring seminal work on national identity. He introduced the concept of a “shared national consciousness” a description of the powerful force that could hold a “national population” together. This collective consciousness could be described as a set of shared information, beliefs, ideas, moral attitudes, and values that operate as a unifying force within society.

At a time of historic political change and socio-economic transition, it is vital that Bhutanese people take a close look at ourselves. After centuries of complete isolation, two and a half centuries of constructing a polity, and 100 years of Monarchy, the people are mandated to take on new responsibilities. Where will democracy take Bhutan and Bhutanese society? In the recent past, the Bhutanese “family” was guided by a Monarch who was a father figure for the populace. Today the people have been given the responsibility for governance. In real terms, this means the functioning of a society. In other words, we are moving from dependence, to independence, to inter-dependence.

The introduction of party-based democracy appears to have highlighted the differences that could become divides. After two general elections Bhutan’s image has suffered. Society seems to require a process of healing and reconciliation so that the next generation can grow up, not linked to political parties such as PDP, DPT, DNT, DCT, BKP, but as a generation with the will and ability to change society, even the world, for the better. While the political mudslinging in Bhutan is nowhere as bad as it is in many societies, Bhutanese society seems to have its own share of hate speech addicts who seem intent on splitting the Bhutanese extended family into gloating “winners” and nervous “losers”.

A society that existed in interdependence with all life forms needs to put politics into the right perspective. It is important that Bhutanese politicians, bureaucrats, businessmen and businesswomen, and farmers learn to agree to disagree. It must be “us and them”, not “us versus them”. If we truly draw from our own wisdom traditions, we will realise that building a national identity is about building a shared future through inclusive values like compassion and tolerance, rather than a policy of exclusion stemming from insecurity.

How is this going to happen?

The answer lies in a narrative that must be drawn through discourse and debate. Bhutan needs a healthy atmosphere of open discourse. Bhutanese society has had no real public discussion on who or what is a Bhutanese. What is this entity called Bhutan? Is it a state? A nation? Is it a nation-state? What kind of society do the people want? What are the issues that are important? What are people concerned about? What are the analyses and perspectives everyone is looking for? What is the future of Bhutan? As usual, there are more questions than answers. Bhutanese must ask some hard questions, and some painful ones, to develop the Bhutanese narrative. Society needs to understand what is and what is not working.

In Imagined Communities, Anderson talked about the critical role that improved communications and education played in creating the shared consciousness in the second half of the 19th century. He referred to the print media that created awareness of common issues. The press has grown into today’s diverse and powerful media whose headlines must identify important issues. When people in the north, south, east, west, and centre read, listen to, and watch the same news and programmes they begin to develop shared concerns and values. Author and journalist, George Orwell, echoed this when he said we need the media to both educate and actively construct public opinion, to induce and promote the public conversation we must hold with ourselves about ourselves”.

Rapid technological development has created the new media and social media that have given citizens a new role to hold responsible discussions. Shared consiousness is the process through which media and citizens define and discuss issues of common interest so that Layaps and Brokpas, Lhotshampas, Sharchhops, Ngalops all share the same concerns. Today’s discourse can be much more inclusive with the Internet providing a much larger public space for real conversation among citizens and that vital exchange can take place only if citizens do not just talk but listen to each other.

From a shared consciousness to a narrative

Eleanor Roosvelt provided a guide to quality discourse when she said “Great minds talk about ideas. Average minds talk about events. Poor minds talk about people.” The task is to make the significant interesting and not the interesting significant.

Today, Bhutan holds some global attention because of the perception that this small kingdom, seeped in wisdom traditions drawn from Buddhism, may provide the inspiration to reverse trends in a world driven by consumerism. Bhutan had turned its late entry into development into an advantage. When the kingdom entered a world that had been through two decades of the development process, spearheaded by the United Nations and other international agencies, what Bhutan saw was that the world had interpreted development purely in terms of economic and material growth. In the pursuit of material wellbeing countries had sacrificed their environment, societies had lost their identities.

It was at this stage that the fourth Druk Gyalpo, His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck, declared that Bhutan’s goal for development was Gross National Happiness, a pun on Gross National Product, thereby providing a higher goal for human development. GNH went global and effectively branded the country. It became an image if not an identity. However, GNH remains a vision for which the narrative has to be written. At a time when global leadership is seeking a path and a vision beyond GDP, Bhutan is being challenged to make Gross National Happiness work at home if it is to inspire an alternative development paradigm.

GNH was the vision of a leader but what is needed is the interpretation and academic construction of this much-needed value system into pragmatic and achievable policies, strategies, activities. It is not the words that are important. It is the ideas. There is substantive work done on three of the four GNH pillars: conservation of the environment; good governance; and sustainable socio-economic development. There is much that Bhutan can learn from work done by governments, the academia, civil society and individuals in these areas. In fact that would give GNH more depth. GNH is interpreted as the physical, social, psychological, and spiritual wellbeing of the people, these being the condition for happiness. If Bhutan is to aspire to such a vision of happiness (read contentment), how do we get there?

The fourth pillar of GNH, Bhutan’s emphasis on preserving its rich culture, is perhaps the most important lesson that a small kingdom with big dreams has offered to humanity. When Bhutan proposed a GNH-inspired New Development Paradigm to the United Nations in 2013, a proposal written by a team of Bhutanese and international academics, the idea was to go beyond GDP and halt the human consumption of the planet that is taking place through excessive materialism. In this process, researchers were reminded that mankind’s search for material progress largely killed distinctive cultures around the world. Today, the loss of indigenous languages is happening at a faster rate than even biological extinctions which, scientists say, are now at 1,000 times the natural rate caused by the loss of habitat.

What else can Bhutan offer? What could a future vision for Bhutan look like? How do we convert the increasingly fallow fields into sustainable agriculture? What is our economic vision beyond hydropower? What is the state of our political economy and the wealth gap when the world is aghast that 50 percent of the global wealth is in the hands of 80 people? How do we ensure a just society with a fair distribution of wealth? How do we design a foreign policy that will strengthen our sovereignty? How do we ensure an inclusive political process?

With the democratisation process, Bhutan has established a political layer of leadership. The bureaucracy is learning to deal with this phenomenon. A private sector is emerging although it is dominated by a few business houses. But where are the creative communities? Where are the artists, thinkers, intellectuals, and the specialised professionals to ensure a balanced society?

A Democratic Constitutional Monarchy

The introduction of a Democratic Costitutional Monarchy, described as a “gift” from the Golden Throne, has set the stage for effective governance. The Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan defines the concept of the Bhutanese state with the King as Head of State. It is in the context of this state that the national narrative must be written. It is from this narrative that the vision for Bhutan must be refined. And it is this vision that will shape the Bhutanese identity.

The process of democratisation has separated the State from the Government because the Government functions within the State. The shared vision is symbolised by the King and upheld by the State. It becomes the responsibility of the citizens who form political parties, elect governments, and function as civil society to help achieve the vision. Politics is the process in which different parties convey their ideas and offer strategies to achieve this vision.

With the development of a shared consciousness the people see the King as a symbol of unity. It is the State from which citizens draw a sense of belonging and trust. National identity is nurtured when people see a fair system to which they want to commit themselves and in which all feel they have a stake. People want a reciprocal relationship with all levels of the leadership. Such are the conditions that will provide the foundation for national sovereignty and guarantee a future brightened by hope.

National identity is established and maintained through an earnest and sustained effort. The Bhutanese identity must be a true blend of the past, present, and future. Even as we preserve our social, cultural, and spiritual memory, we must adapt to the reality of rapid change. We must draw on the creativity that new and powerful tools like Information Communication Technology enables. Bhutan’s strength must be its people who are now making the transition from being loyal subjects to responsible citizens. Since change is the only constant, we want to become a society that learns to learn.