What would a 21st century Bhutanese identity be?

You can download this Article as a PDF by clicking here

Our inheritance

Bhutan’s journey from the 20th into the 21st century is one that the Bhutanese take great pride in. Our Fourth Druk Gyalpo regarded as a wise, skillful and compassionate leader worked tirelessly to build on the foundations laid by His predecessors, leading the country to where it is today as a sovereign and peaceful nation.

The hallmarks of His Majesty’s hard work are well known. They include, among others, gradual but deliberate reforms beginning with decentralisation processes in 1981 and 1991 respectively; followed by devolving executive powers to an elected Council of Ministers in 1998 after which the drafting of the Constitution was initiated and the consultations with the people on its finalisation took place. After leading the Bhutanese army to flush out Indian insurgents and securing Bhutan’s security in 2003, His Majesty in 2006 voluntarily abdicated to the disbelief of a highly emotional citizenry.

These processes culminated in the successful institution of a Democratic Constitutional Monarchy in 2008. His Majesty the Fifth Druk Gyalpo assumed responsibility as the guardian and protector of the nation. The first democratically elected government took office in the same year. In addition to cultivating a national identity and the spirit of democracy to strengthen the nation’s sovereignty, the Fourth Druk Gyalpo also gave expression to Gross National Happiness (GNH) as a higher vision for Bhutan’s development.

As such, the Bhutanese people have entered the 21st century with more opportunities at hand than ever before. As our elders remind us, we are fortunate kewa zang nu and we have much to be grateful for, being Bhutanese. Often we forget, however, that with these opportunities come responsibilities- responsibilities such as taking the nation forward beyond basking in the achievements of our parents.

This article addresses the question of what it means to be a Bhutanese in the 21st century, from the perspective of our role as citizens enjoying this rich inheritance. To have a clear sense of what makes us Bhutanese today requires that we first take an honest look at where we are currently heading as a society and culture. It demands that we be cognisant of the multiple realities associated with being a part of the larger global community. Finally, it reminds us that hard work and integrity are still necessary if we wish to contribute to building a happy and just society, in accordance with our nation’s vision of GNH.

Our current state

A culture in transition

Bhutanese society and culture are at a critical juncture today. The younger generations of Bhutanese have to navigate a more fluid, and at times a more confusing, socio-cultural environment than the previous generation. Of course change is constant and it is not that Bhutan has remained static up to now. But the older generations of Bhutanese probably exhibited a clearer sense of belonging and identity, living as they did in accordance with local cultural traditions as a matter of daily life.

The point is that in Bhutan, as elsewhere, the pace of socio-cultural transformation has been phenomenal largely because of the strides in Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) and its pervasiveness over the last two decades. For Bhutan, the impact of shedding our geographical and mental isolation from the so-called “outside world” is becoming more obvious by the day.

At the most visible level, we see our youth’s preoccupation with sporting “Korean hairstyles”, wearing low-hanging jeans mid-way across the buttocks, an appetite for ear-splitting heavy metal music, and an eager display of hip-hop freestyle dance moves at the Thimphu Clock Tower Square. We have also altered the way we wear our gho, kira and tego several times in an attempt to marry comfort with fashion.

Often, our elders are left perplexed with these trends while traditionalists are offended, and we are quick to deride our youth for failing to uphold our culture and tradition. In the process, we get detracted from addressing the deeper undercurrents that such trends are symptomatic of.

Erosion of awareness

I would say the real “threat” to our culture and identity is the subtle erosion of our sensibilities and the psychological disconnect that this creates in our homes and communities. Our sense of belonging to our communities and confidence in our cultural heritage is being tested by the hypocrisy that we are both a witness to and a part of. Inevitably, our desire to explore and experiment with other means and expressions of identity is compounded whether it is in the course of coming of age as an adult or in transition to grandparenthood.

Thus, for example, on the one hand, we take great pride in the richness of our “living” cultural heritage and traditions, upheld in the form of dzongs, lhakhangs, goendeys, dances, songs, cuisine, and festivals; on the other, the purpose and significance of much of what we do in the name of culture and tradition is often lost in translation. Their significance is no longer as evident to the average Bhutanese today as it was in the past.

Many, especially the younger generations of Bhutanese, now perceive an imbalance in the emphasis placed on the visible forms of culture as compared to the amount of thought given to the intrinsic values that these forms supposedly embody. So while we are told that our inner values and attitudes shape our external behaviour, we see how convenient it has become to make a great show of “proper” cultural conduct when our actual motivation and attitude are entirely different.

For example certain aspects of Driglam Namzha, like who gets to wear what colour kabney or the use of honorific titles like dasho, have become more a subject of ridicule than appreciation because the purpose of this code of conduct and etiquette is seen to be reduced to a mere display of social status, minus the honourable behaviour that is expected. And though we boast about Tha damtshig and ley jumdrey1 as the essence of traditional Bhutanese value system, there are also too many instances of nepotism, corruption and other acts that harm our public system and society.

An additional challenge is exemplified by the state of indigenous languages in Bhutan today. As Karma Phuntsho, a leading Bhutanese scholar, describes in his book The History of Bhutan:

“…most educated Bhutanese are struggling to juggle between linguistic multiplicity and mastery.” Although most Bhutanese “children still grow up speaking multiple Bhutanese languages…the predominance of English, especially in the written medium, poses a serious challenge…As each word represents an idea, the death of each language will mean the loss of a whole set of ideas and culture.”2

The situation is not made any better when we have our schools and media passing on confusing messages to impressionable young minds as to what constitutes Bhutanese culture. To give one example, there is a curious phenomenon of educational institutions in the capital choosing to stage what they call a “cultural bonanza”3 for the entire duration of their annual school concerts year after year; and the local TV stations faithfully recording and regurgitating these shows over the airwaves.

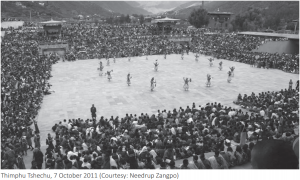

The psychological disconnect from our traditional values and practices only get wider, as we are further challenged by different worldviews and assumptions imported in the form of secular education models from more materially advanced societies. So for instance, we sense a certain apathy among many Bhutanese today towards religious ceremonies and rituals. The spiritual benefits of traditions like tshechu4 are also lost on many “educated” Bhutanese who sometimes view these vital aspects of our society as superstitious, primitive and outdated in the face of modern science.

Then on the flip side it is known, for example, that some of our educated men who supposedly know better than their village counterparts have no qualms taking advantage of a certain traditional courtship custom practised in eastern and central Bhutan. Known as Bomena in the locality of an enthographical study carried out by Bhutanese anthropologist Dorji Penjore, it is traditionally “an institution through which young people find their partners and get married”.5 Unfortunately, it has become a widely misunderstood custom subject to abuse. As the author notes in his study:

“It is mostly visiting government officials or urban visitors who misuse the Bomena custom, exploit their social statuses and use financial reward to deceive village girls into having sex, even to the extent of making false matrimonial promises….Bomena within the context of a village endogamy is a socially regulated practice but it becomes a problem if it is misused by the non-village residents for reasons other than courtship.”6

Meanwhile in urban circles, our inability to move the discussion beyond heated debates on the inaccuracy and offensiveness of using the term “night hunting” to describe this custom delays the real issue from being addressed i.e. that gullible village girls are being taken advantage of and children are left fatherless.

And finally, while we say that Buddhism is deeply ingrained in Bhutanese society, our inability to tread the “middle path” says otherwise. We have adopted an “us versus them” mentality in our approach to the discussion of party politics, often with the result that anyone trying to find the middle ground is quickly condemned for being on “the other side”.

Such tendencies are not entirely new of course, as we know from stories of the beloved “divine madman” or Drukpa Kuenley7– a classic and timeless reminder of society’s tendency for hypocrisy. What we see in this century though, is an intensification of this common human trait and a quicker erosion of our sensibilities as we interact more and more with the cultures of consumerism, greed, instant gratification and sensationalism.

Exploitation of GNH

To complicate matters further, who we are as a nation and a people is increasingly being tagged to a Shangrila-ised notion of the Gross National Happiness (GNH) concept, at a time when we are still trying to understand what it should really stand for. Attempts by local scholars and policymakers to define and communicate the idea have been inadequate and are yet to find common ground.

In the early days, when we ourselves never made such bold claims, the international media was largely responsible for creating a romanticised picture of Bhutan as “the happiest country in the world” and as “the last Shangrila”. However, the scenario is very different today. We Bhutanese have been quick to jump on the bandwagon, as can be seen from the evolution of marketing strategies employed by tourism and related businesses in the country over the past decade.

We now see exclusive and expensive package-tours tailored specifically for visitors to “experience GNH” through an assortment of intellectual discussions and “mindfulness” programmes, as though that is all there is to GNH. At one point, the national airline Druk air carried their duty-free shopping magazine, splashed with the title “Happiness duty free shopping”. To top it all up, the Tourism Council of Bhutan adopted the tagline: “Bhutan: Happiness is a Place”.

Meanwhile, over the last decade, we probably got carried away so that GNH (and Bhutan along with it) came very close to becoming a rubberstamp for everything under the sun; putting the concept at risk of standing for nothing in the end and becoming the empty slogan that its critics claim it to be.

We took it as our mission to formulate a new development paradigm for the global community to replace the dominant growth-based paradigm with, and thereby “save the world” from imminent self-destruction. Given the profundity of GNH, the initiative in itself was a noble one. As it is said in the language of Buddhist teachings, we wanted to work for the “benefit of all sentient beings”. But as it is also said, sometimes, we must first liberate ourselves before we can liberate others.

Those who have been involved in the theorising and dissecting of GNH will admit, that the whole exercise of developing measurements for GNH also came out of the notion that we have to rise to the challenge of demonstrating its applicability in quantifiable terms to an international community of scholars.

Of course the choice was ultimately our own, and the government of the day adopted the view that GNH, like the GDP (Gross Domestic Product) indicator, must be measurable so as to track and assess the government’s performance in delivering happiness ± which is paradoxical because the expression of GNH itself was supposed to challenge the status quo of how progress is viewed, approached and communicated.

So it is ironic that while the internationalisation of GNH has served to inspire people from all walks of life around the world8 , we in Bhutan are suffering from greater confusion and complacency.

The hasty packaging of anything and everything as GNH without giving the idea serious thought and work it deserves is yet another example of a profound Bhutanese cultural expression getting hijacked by the degradation of our sensibilities and our tendency for hypocrisy. As creatures of habit, within a short span of time, we managed to overlook the underlying wisdom of GNH in its simplicity.

It is the perpetuation of such idiosyncrasies that has contributed to a certain sense of alienation across Bhutanese society. When such subtle, yet fundamental, disconnects are gradually intensifying in the so-called “modern” Bhutanese psyche, we may unconsciously be chipping away at the very essence of our nationhood.

Moving forward as a 21st century Bhutanese

So what do we do?

Well, the Bhutanese in general are a proud lot, even as we profusely display how humble we are. So it is likely that most of us would like to uphold a decent image of Bhutan to the world. But more importantly, many of us also love our country deeply, and do actually care about the health of our communities.

Therefore, it is possible for us ± as parents, teachers, spiritual leaders, politicians, civil servants, and all other role models to our youth ± to be a little more sincere about our intentions and do away with the habit of treating important elements of our cultural heritage, including GNH, as convenient eyewash for our own selfish interests. By taking it upon ourselves to carefully reflect on the opportunities and responsibilities bestowed on us, we can begin to work towards cultivating a Bhutanese culture that is more meaningful and of greater benefit to our nation in the 21st century.

The vision of GNH offers enormous potential in this regard. At one level, it represents the challenges and prospects of a nation and people grappling to find the middle ground between spiritualism and materialism, and between tradition and modernity. At another level, GNH as it is enshrined in our Constitution9 , represents the opportunity that exists for us to cultivate a “culture of GNH’”and to work towards building a “GNH society”.

Therefore, it is up to us, the Bhutanese of today, to revive not just the inspiring quality but also the realistic quality of GNH as an authentic representation of Bhutan and the Bhutanese persona in the 21st century.

Valuing the wisdom of our parents

We have to recognise that, during the reign of the Fourth Druk Gyalpo, the understanding and application of GNH was largely intuitive. Now, in keeping with the times and in view of the kinds of challenges we are facing, it is a vision that demands more specific goals and frameworks for its practical application. This requires that we go back to basics and clarify for ourselves the underlying values of GNH.

It is beyond the scope of this essay to delve into any meaningful detail as to what these values are; but the main purpose here is to remind ourselves that we must look to the wisdom already available to us, as the starting point. So for instance, we look up to the example set by the Fourth Druk Gyalpo, who is regarded as the “propounder and custodian of GNH”10.

We see that GNH as expressed in the 1970s summed up the priorities of a relatively young nation state as it set about handling its integration in the global community on its own terms. While it knew that development is a national and a human necessity, it also saw the negative societal impacts of both the means and objective of development as practised outside our borders. As such, “gross national happiness” (read “wellbeing” or “contentment” of society) was to be Bhutan’s yardstick for progress rather than GNP (Gross National Product).

What later came to be dubbed as, “the four pillars of GNH”, were in fact priority areas that gave direction to Bhutan’s development processes before GNH even caught on as a fashionable acronym. Conscious decisions had been made early on, to conserve the environment, promote culture, establish systems of good governance, and promote socioeconomic development that is balanced and equitable.

Such an approach to development tells us that the principles of “justice”, “equity”, and “cooperation”, tying in with the Buddhist notions of “interdependence”, “compassion” and “the middle path” were emphasised. Upon proper reflection, we can see that these core principles and values are even more relevant for us today.

We are still experiencing certain “growing pains” as a relatively young democracy, and our interaction with ‘modern’ developments are testing our affinities to our various communities more than ever before. Given the deep influence of Buddhist philosophy on our culture, the basic tenet that we cannot be truly happy as long as there is suffering around us is one that we should be acutely aware of. So it is in this spirit that we must come together, and channel the values that matter most to us into a coherent vision for adoption at all levels of society.

Respecting evolving contexts

As we go forward in the 21st century, GNH reminds us about the necessity of reflection and awareness of our own evolving contexts, so that we make (quoting His Majesty the King) “wise decisions for a better future”.

Therefore, we need to be aware of our special geo-political situation in the region. In view of the circumstances under which Bhutan was unified as a nation state and had to maintain its sovereignty, the idea of a Bhutanese national identity has been integral to our very existence since the time of Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal in the 17th century. Situated as we are between the two most populous nations in the world, and in the absence of economic and military might, Bhutan’s cultural resilience and national identity derived from the diversity of its many local cultures will remain our greatest strength.

That our cultures and sovereignty are inextricably intertwined with our national identity is a reality that we must accept.

At the same time, we must also accept that we are in an age of rapid globalisation. While trying to make sense of this newer reality, it may seem at times that we must all become “global citizens”. This is a fair notion but we need to be mindful of what it means. Often we mistake “being global” for a romantic notion, that all the peoples of the world should come together in a mishmash of identities and form a kind of cocktail “universal culture”. This would be neither useful nor desirable as we risk losing our authenticity; and in the process we would be doing great disservice to humanity by depriving it of the beauty and meaning inherent in its complexity and diversity.

At the same time, we must also accept that we are in an age of rapid globalisation. While trying to make sense of this newer reality, it may seem at times that we must all become “global citizens”. This is a fair notion but we need to be mindful of what it means. Often we mistake “being global” for a romantic notion, that all the peoples of the world should come together in a mishmash of identities and form a kind of cocktail “universal culture”. This would be neither useful nor desirable as we risk losing our authenticity; and in the process we would be doing great disservice to humanity by depriving it of the beauty and meaning inherent in its complexity and diversity.

However, maintaining our authenticity is not about being a cultural purist or chauvinist. As the timeless Drukpa Kuenley reminds us, that kind of attitude can set us up for all kinds of hypocritical behaviour. Rather, it is about accepting the diversity that exists in the world in all its forms; and within that we are grounded and secure in our own identities.

So in the midst of enticing trends from other cultures and societies, we must remain grounded in some basic values of our own. Tha damtshig and ley jumdrey- the bedrock of the Bhutanese value system ± must be upheld and nurtured even as we seek positive values to emulate from other sources. It is in recognising and appreciating the wisdom in our own traditions that we can begin to develop greater appreciation for the wisdom offered by other traditions and cultures.

The point is that in diversity we find unity, and vice versa. So while we are united by the strength of a national Bhutanese identity and a clear value system, we also flourish because we can appreciate and draw inspiration from a diversity of local and global cultures and communities- be that through ties of kinship, friendship, ethnicity, religion, language, art, music, fashion, gender, sports, associations, or professions. When we respect this simple fact, we can coexist in harmony and unity.

Assuming responsibility as a GNH citizen

As a unifying force and guardian of the nation, the institution of Monarchy has been and remains our core source of inspiration. And as true Sons of the Palden Drukpa11, the Fourth Druk Gyalpo and His Majesty the King evoke in us strong emotions of national pride and duty at mere sight and speech.

The youth today especially identifies themselves with His Majesty the King, who is fondly referred to as “the People’s King”. As the protector and upholder of the Kingdom’s Constitution “in the best interest and for the welfare of the people of Bhutan”12, He represents the aspirations and responsibilities of a new generation of Bhutanese.

However, to “be the change we want to see”, it is ultimately the people of Bhutan who must work together in a spirit of cooperation. Under the guidance and inspiration of His Majesty the King, each of us must play our part to support the government, bureaucracy, civil society, and other members of our communities to “walk the talk” of GNH. As times change, it is up to us to seek and provide the relevant examples and initiatives that make an effort to do just that.

The younger generation must have access to the repositories of knowledge, insight and experience of nation-building so that awareness and appreciation for our heritage can be maintained and enhanced. Therefore, our various institutions including those of family, education and spiritual traditions must assume greater responsibility in providing the necessary mentorship to our children.

Let us also remember that our Constitution is the culmination of the legacy that is Druk Yul in the 21st century. Therefore, to be a responsible Bhutanese in this century and beyond, we refer to it for basic guidance. And in keeping with the times as well as the words of our teachers, we must encourage critical thinking and enquiry, and conduct our debates respectfully as we work together on weaving GNH as a cultural consciousness of Bhutanese society.

As His Majesty the King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck has said:

“Our nation’s Vision can only be fulfilled if the scope of our dreams and aspirations are matched by the reality of our commitment to nurturing our future citizens.”13.

References

1The concept of Tha Damtshig encompasses essential values like mutual trust, duty, and sacred commitment to others in society; and Ley Jumdrey is the understanding that all actions have consequences so that good begets good and vice versa.2 Karma Phuntsho. The History of Bhutan (Pg. 61), Random House India, 2013.

3 Over a decade or more ago, school concerts usually staged a variety of programmes including a balanced mix of Bhutanese as well as ‘foreign’ plays, skits, songs, dances, etc. These days, the variety has disappeared and has been replaced primarily with a non-stop mix of dances; most of the numbers are danced to so-called “modern Bhutanese songs” in a hybrid of dance steps, some hip hop and freestyle, and a minority of Nepali, Tibetan, Indian and traditional Bhutanese dances.

4 Tshechu, literally meaning day 10 of the month, is the festival conducted in honour of Guru Rinpoche who brought Buddhism to Bhutan in the 8th century. Tshechus are conducted all over the country but generally on or around the 10th day of the month in the Bhutanese calendar.

5 Dorji Penjore. Love, Courtship and Marriage in Rural Bhutan: A Preliminary Ethnography of Wamling Village in Zhemgang. Galing

Printers and Publishers, Thimphu, 2009.

6 Ibid.

7 Drukpa Kuenley was a great Tantric Buddhist Master, yogi and a patron saint of Bhutan from the 15th-16th century.

8 At a time of growing dissatisfaction with the global governance systems of a growth-based worldview, many see the potential in GNH as an inspiring alternative.

9 Article 9 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan states that: “The State shall strive to promote those conditions that will enable the pursuit of Gross National Happiness.”

10 This phrase has been quoted from the description of the characteristics of the Fourth Druk Gyalpo as signified by the logo

commemorating His 60th birth anniversary – (http://www.kuenselonline.com/60th-bcc-logo-launched/#.VH36S0sxElI).

11 Palden Drukpa can basically be understood as “Glorious Bhutan.” 12 The Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan, Article 2.18.

13 His Majesty the King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. Address at the 3rd convocation of Royal University of Bhutan for Samtse and Paro Colleges of Education, February 17, 2009. Accessed from: http://www.bbs.com.bt