Bhutanese Women in Politics: Myths and Realities

Policy and Legal Framework (At National and International Level)

Bhutan has given due importance to increasing women’s participation in development activities, elected offices and decision-making positions. A review of the five-year plans indicate that, while a gender-neutral position had been maintained by the Government in its policies, plans and programmes, it slowly evolved from a Women in Development approach in the 1980s to a gendered approach by the 10th Five-Year Plan (2008-2013).

Key legal and policy frameworks have been adopted to ensure women’s full and equal participation in the political, civil, economic, social, and cultural life. A Royal Decree was issued in 1998 that stressed the importance of women’s representation in the National Assembly. The 2008 Constitution under Article 7 (15) states that: “All persons are equal before the law and are entitled to equal and effective protection of the law and shall not be discriminated against on the grounds of race, sex, language, religion, politics or other status.”

The National Plan of Action for Gender (NPAG) which was implemented in the 10th Five-Year Plan, reinforced the promotion of women’s participation in politics, and identified interventions and targets for enhancing women’s participation in politics.

The 11th Five-Year Plan (2013-2018) moved one step further by establishing “Gender Friendly Environment for Women’s Participation” as one of the 16 National Key Result Areas, with “Draft legislation to ensure quotas for women in elected offices, including the Parliament and local government bodies” as one of the key performance indicators.

The 12th Five-Year Plan, which will be launched in 2018, has “Gender Equality and Women and Girls Empowered” as a National Key Result Area with key performance indicators and targets that will measure women’s representation in Parliament and local government.

The National Plan of Action to Promote Gender Equality in Elected Office (NPAPGEEO) was also developed in 2015, and includes actions to enhance women’s participation through awareness and capacity building, as well as propositions to have temporary special measures in place.

Women’s rights to equal political and public participation, and the broader principle of gender equality, form a critical component in several declarations, conventions and other international norms. The Beijing Platform for Action 1995 put forward the “positive action” agenda, providing a crucial link between democracy and participation of women:

“Achieving the goal of equal participation of women and men in decision-making will provide a balance that more accurately reflects the composition of society and is needed in order to strengthen democracy and promote its proper functioning.” (Art. 183).

Article 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) & Article 25 of the International Covenant of Civil & Political Rights (1966) underscore not only the right to vote but to be elected through free & fair elections.

The Convention on the Political Rights of Women (1952) calls upon states to ensure that women are eligible for election, at par with men, without any discrimination.

Article 7 of the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), explicitly states the responsibility of “state parties to eliminate all discrimination against women in being eligible for election to all publicly elected bodies”.

Target 5.5, under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), strives to “ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in politics, economy, and public life”. A deadline of 13 years is put forth to achieve 50-50 by 2030, that is, to ensure women’s full, equal, and effective participation. It is not enough that women are present in governance; they must also be empowered to be effective and hold leadership positions.

Bhutan is currently midway through implementing the 11th Five-Year Plan, which includes gender equality as a key element for strengthening governance. Although Bhutan appointed the first female Minister after the second parliamentary elections in 2013, the number of elected female representatives in Parliament and in local government has decreased, despite strong commitment and political will.

“Success without democracy is improbable; democracy without women is impossible.” ~Madeleine K. Albright

Myth vs Reality of Women’s Political Participation in Bhutan

The myth of “equality” and the “invisible” reality?

In the land of Gross National Happiness (GNH), a majority of the population is female, and matrilineal customs dominate in many communities. Women inherit family assets and pass them down from mother to daughter. Women are said to be “in charge” and gender relations are highly (and genuinely so) egalitarian. Why, then, are there only four elected women MPs in the 2nd democratically elected Parliament of Bhutan (2013-18)?

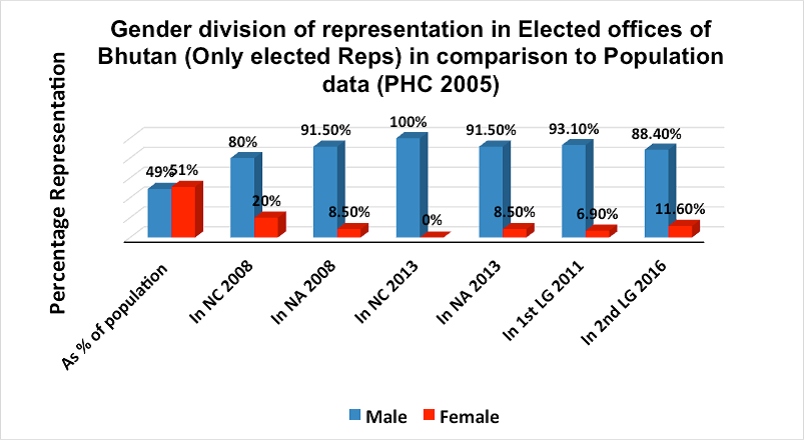

Why are there only 8.5 percent of seats in the National Assembly representing women, who comprise 51 percent of the population? Why do the other 49 percent of the population need 91.5 percent of seats to represent them?

To add salt to the wound, all 20 dzongkhags in the National Council (NC) Elections of 2013 elected only men, except for His Majesty The King’s benevolent appointment of two women as Eminent Members. The National Council is the House of Review of Laws and Policies. The people of the constituencies of the five women candidates standing for the NC considered them not capable enough to serve. Three of them were re-contesting, as were several male colleagues. Such is the level of confidence in women.

The situation is similar in the 205 Local Governments, with two women gups (head of gewog) struggling to stand tall to be “seen” alongside 203 male gups, Women’s voices can barely be “heard”. This is a highly unbalanced scenario.

The myth and reality are not in sync, more so when examining this aspect of women in governance, leadership and politics.

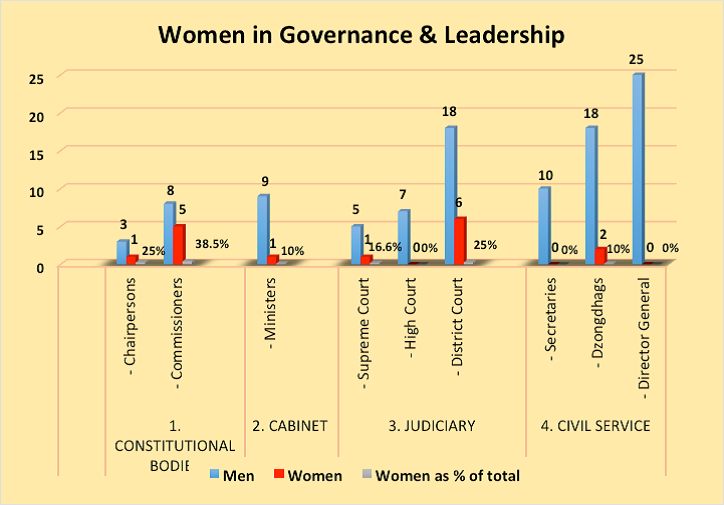

Source: BNEW 2017

How do we explain that when Bhutan projects a progressive image of a happy, balanced and harmonious society, where women are empowered and enjoy full equality with men, where women are respected and daughters “favoured”? In reality, women are “invisible” and hence “voiceless” in the prestigious halls of Parliament and the highest policy-making bodies.

Why is the reality on the ground full of gender stereotypical values, norms, attitudes and mindset that covertly and overtly stand in women’s way when they reach out for leadership positions in every sphere, in contrast to the myths of a supportive society?

Why do women lack confidence to step out and stand up? Why are women not trusted to lead in the public sphere, even though she can be fully trusted to run and manage the home front? Why are women constantly discouraged from stepping out into the public sphere, which is kept as a space for men only?

The seemingly convincing arguments of the 1970s to 90s — when girls were loved, favoured and kept at home (and hence at a disadvantage today) —no longer hold much water. The narrative has changed and so have women.

Society must recognise this and be more accepting of women in the public and leadership spheres. We should not expect women to stay home, playing expected gender roles that ask of them to be docile, unambitious, uncreative and hence suppressing (and wasting) all their potential, intelligence and wisdom.

Are We a Matrilineal Society Doomed by Patriarchal Norms?

Today, owing to the mismatch of myth and reality, the situation of Bhutanese women is not starkly different from elsewhere. In the not too distant past, Bhutanese women by custom were always at the helm of things and strongly positioned in the family, community, and society. We were definitely not without traces of patriarchal norms and values, but there were other forces that kept it in balance, resulting in the gender-egalitarian relations between men and women in, which we continue to take pride.

With the passage of time, and with “development”, “progress” and “modernisation”, we seem to be (unknowingly and unquestioningly) in the race to become more and more like the rest around us. Patriarchal values and norms have started to become more prominent even in a matrilineal society like ours. Most of us, including women, believe that leadership roles belong to men, and a woman is best at home. These beliefs are universal, but is it not true that Bhutan is different and unique? Is it possible that Bhutan could again become different and move back to its roots of a Buddhist society which believes in leadership of women and female wisdom?

The first democratically elected Parliament of Bhutan (2008-13) had eight elected women (four in the NA and four in the NC).

Combined with two women appointed by His Majesty The King in the NC, women’s representation for the period stood at 13.88 percent. Ten women versus 62 men! This could be compared with the global average of women in Parliament of around 22 percent.

But the number of elected women was halved in the second parliamentary election in 2013, to four women MPs in the Parliament. No woman was elected to the NC, save for the two women Eminent Members appointed by His Majesty The King, whereas the NA maintained the same number of four women MPs. So, today four plus two women MPs represent nearly 51 percent of the population in the Parliament of Bhutan. Is this adequate? Is this good enough? Is this a desirable trend and element in the young Bhutanese democracy that must be nurtured, or “nipped in the bud”?

Some countries, like Denmark, took 100 years to achieve close to 40 percent representation of women in Parliament. Do we want to wait for 100 years too? Should and could Bhutan achieve more at a faster pace than Denmark? Are we capable of doing better in keeping with our own values and principles, guided by the GNH philosophy of development, which conveys a different message altogether, of a Bhutan where women are empowered, “in control”, and enjoying equal rights and freedom with men.

Secretary General of the IPU, Martin Chungong, says that “Parliaments are crucial to ensuring women are among the world’s most high-profile leaders and to strengthening the policies and legislation needed to meet the goal of gender equality and women’s full and equal participation at all levels by 2030”. He adds that “it is time for more ambitious measures to take women’s participation and political voice to the next level. A great deal has been achieved in recent years, but more needs to be done to effectively embody gender equality, and deliver it”.

Political Participation of Women in Bhutan

Why stress on women’s political participation?

Disproportionate representation in decision-making translates into underrepresentation of issues, or one-sided “shows”.

Simple math shows that four women MPs are representing 357,000 Bhutanese citizens who are female, and 63 men represent the remaining 343,000 citizens who are male. This is nothing short of under-representation of women in the Parliament of Bhutan, as shown below:

Source: BNEW

When 50-51 percent of the population are not represented proportionately in decision-making, how can laws, policies, budgets, and development as a result be as balanced, holistic, comprehensive and inclusive as we desire or claim? When women are not “seen” in the corridors of power and leadership, how can they grow to their full potential? How can women learn to lead? How can society be convinced about their ability to lead? In the absence of women’s voices, how can the feminine side of concerns, issues, and needs in development be fully addressed?

Unseen is Unheard

In governance and politics, women’s participation is more than a matter of “political correctness”, fairness, or equality. Gender balance in decision-making has a direct impact on a nation’s stability and ability to grow and develop. We know from developments in other parts of the world that when women share decision-making power with men at higher levels, countries experience a higher standard of living too. Positive developments can be observed in key areas that fuel economic development, such as education, health and infrastructure.

It is well documented nowadays that women’s participation also results in tangible gains for democratic governance and higher levels of satisfaction among the electorate regarding how a government is performing. When there is greater gender balance in government, voters tend to experience greater responsiveness to their needs, and in times of conflict, women are better able to negotiate and sustain peace.

Even political parties that take women’s participation seriously stand to gain on a number of fronts. Most significantly, female voters outnumber male voters in most countries, including our own. So women voters do hold the potential to deliver the margin of victory in many elections, for parties that take their issues seriously. Women are also more likely to work across party lines and strive for consensus and cooperation.

There is also substantial evidence to suggest that gender-balanced decision-making bodies, including boards of governors, executive committees and judicial bodies, function better.

Temporary Special Measures

Special measures to increase women’s effective participation in governance

“Equal consideration for all may demand very unequal treatment in favour of the disadvantaged.” ~ Amartya Sen.

Bhutan ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in August 1981 without any reservations. As required by the Convention, periodic reports on the status of women are submitted to the UN CEDAW Committee every four years, and the Committee forwards its recommendations to the state party.

Bhutan has submitted nine reports so far, and every time the recommendation has been for the country to adopt temporary special measures to address the gap in women’s political participation. As a result, the NPAPGEEO was developed through a consultative process, with the objective of putting measures in place to enhance the participation of women in elected office.While part of the Action Plan is already being implemented, there is little progress on temporary special measures, due to legal implications. The next action in the pipeline is to carry out a review of the NPAPGEEO, with the participation of all key stakeholders, to come up with an effective and achievable action plan.

Countries around the world have developed and implemented temporary special measures, quotas, affirmative action, multi-sectoral measures addressing education, economic empowerment and ending violence against women, and fast-tracked systems of inclusion. The key idea behind such affirmative actions and measures is to address the structural barriers, subtle biases and gender differences that women face.

Depending on the local context, more than 80 countries have adopted varied electoral gender quotas by law. There are two types of gender quotas:

- Candidate quotas are set most commonly in Latin America and Europe, through the gender composition of candidate lists

- Reserved seats are most commonly used in Asia, the Arab region and Sub-Saharan Africa to regulate the gender composition of those elected.

France adopted a candidate quota by law system through the gender quota law in 1999, making it one of the first countries to adopt such a law that required 50 percent of all candidates nominated by each party to be women. This was closely followed by Argentina with the introduction of candidate quotas by law in 1991 requiring 30 percent of the candidates to be women.

Reserved seats quota by law have been adopted by Uganda, Jordan and India. In Uganda, special district seats are reserved for only women to compete. Jordan reserves 15 seats and follows “the best loser system” to select women who got the highest votes but were not elected. India reserves 30 percent of the seats for women in the local government elections. Australia adopted voluntary quota in 1994 and uses a 35 percent voluntary quota system.

In Bhutan, the three National Consultations and two Conferences on Women in Politics held between 2013 and 2017 put forth the need for a Strategy and workable Action Plan. The National Plan of Action to Promote Gender Equality in Elected Office (NPAPGEEO) was developed as a temporary special measure. It included the following:

Part A: Identifies and prescribes measures for creating a demand for women’s participation.

Part B: Focuses on a variety of interventions, such as creating awareness, and capacity-building, while providing the necessary support to create a level playing field to ensure that a consistent and adequate number of women contest the different elections.

The adoption of quotas has met with mixed reactions from both women and men in Bhutan. During the national conferences and consultations, it was felt that having a quota for women in elected office undermined the capacity and competency of women, and quotas alone would not be adequate to address the issue. On the other hand, some felt that if we were to wait till there was a change in the mindsets of people, it would take us a long time. Further, since there was a need to have role models to encourage female representation in elected office, the adoption of a quota system was felt to be crucial as a temporary special measure.

The Way Forward

According to two studies that were conducted — Women’s Participation in Local Governance (NCWC 2011) and Improving Women’s participation in Local Governance (RUB 2013) — the following factors have been identified as constraining women’s political participation:

- Education and training

- Confidence levels

- Functional language skills

- Double or triple burden

- Attitudes and stereotypes

- Inadequate enabling environment for women’s empowerment, and

- Election system and processes.

The 2nd Conference on Women in Governance, Leadership and Politics, held in Thimphu in March 2017, highlighted the following strategies for increased participation by women:

- Legislative reforms

- Mechanisms to achieve the SDGs

- Sustainable media campaigns

- Partnership with civil society

- Support groups

- Involvement of diverse groups

- Reservation of seats/quotas

- Increased awareness and capacity building, and

- Increased investments.

As discussed in the above conference, measures, and interventions to enhance the participation of women in politics would require a number of targeted special measures and actions on multiple fronts:

» Expanding the pool of qualified and capable women to run for elections;

» Transforming gender norms so that women leaders are accepted as legitimate and effective;

» Supporting women leaders in gender-sensitive political institutions;

» Creating an enabling legislative and policy environment to enhance women’s participation;

» Establishing support systems for women candidates, such as flexitime, childcare provisions and breast-feeding facilities for candidates, voters and those in elected office;

» Awareness and advocacy programmes on gender equality, and promoting a gender-sensitive media;

» Portrayal of women leaders as role models through media; and

» Ensuring gender-responsive school curriculums and school environments.

The Thimphu Declaration drafted and endorsed on the third and final day of the 2nd National Conference entailed the Vision “Planet 40-60 by 2030 in governance, leadership and politics”:

Thimphu Declaration Goals

Goal 1 (2018-2019): Ensure 30 percent of women candidature in the upcoming elections by political parties.

Goal 2 (2020-2021): Increase the number of women elected local leaders by 30 percent using fast track measures.

Goal 3: Increase the number of women executives and leaders in civil services/ public service by 25 percent by 2025.

The measures to realise the three goals comprise of creating an enabling environment for participation of women in politics, including review of legislation, formulation of policies, mainstreaming gender in political party charter and manifesto, conduct of targeted gender-responsive advocacy by media and CSOs, mentoring of aspiring women candidates, putting in place a gender-responsive election environment for increased voter participation turnout, and provide crèche and childcare facilities during elections and in public offices.

In the review of the NPAPGEEO, the recommendations of the conferences and the consultation meetings will be considered, including the adoption of temporary special measures to increase women’s participation and representation in elected office.