Bhutan’s Journey to Economic Transformation

Path of Economic Progress in Bhutan: Retrospection

Our development philosophy has never considered economic growth as an end in itself, nor has it been viewed as a panacea for any ills that may threaten the holistic socio-economic progress of the country and well-being of its people. It is nevertheless deemed essential to achieve GNH, the ultimate goal of the development process. In the process, however, Bhutan continues to be an aid-driven and import-dependent economy, after six decades of development efforts.

Driven by the hydropower sector, Bhutan performed remarkably well in terms of growth. Over the past decades, the average GDP growth rate was about seven percent per annum, making Bhutan one of the fastest growing economies in South Asia. The per capita income witnessed a manifold increase from around USD 436 during 1980-89 to USD 2,879 in 2016. This was a result of dedicated efforts made by our visionary leaders.

Planned economic development laid a strong foundation for a modern economy. From the first to the fourth Five-Year Plans (1961 to 1980), emphasis was given to developing necessary economic infrastructure for development, through the promotion of agriculture, industry, health and education sector. But, three decades later, the present generation is discussing the same priorities, even as the country transits from the LDC status.

Where did we go wrong, and why? With the current economic and political transformation, there is a renewed aspiration to take the economy down a more sustainable path of development. A new era of modern technology has raised expectations. Today, Bhutan stands at a new crossroad in economic transformation. Some pertinent macroeconomic challenges compel us to revisit our triumphs and look at our failure to achieve holistic economic development, in a way, that will be relevant and meaningful for all generations to come.

Growing youth unemployment, continued dependence on aid and imports, persistent structural and supply bottlenecks, and uneven distribution of income are some of the visible challenges for today’s generation. A strong dynamic and progressive economy is required to secure the destiny of our future generations. The economy must transit from dependency to self-reliance through the development of the Cottage and Small Industry (CSI) sector, with hundreds of new good jobs and businesses.

The Journey Forward

Bhutan’s journey forward must be well planned and calibrated. Economic prosperity is difficult but not unattainable. The lessons from advanced economies of the world provide a first-hand experience for our educated generation, to visualise the meaning of our development efforts more holistically, looking through the lens of self-reliance, productivity, and sustainability. Our own cultural values must not be undermined as we live up to the national goals and aspirations that represent the vision of our Kings.

Despite our successes, the renewed focus on economic transformation has become critical to fill the vacuum in today’s economy, including low domestic productivity, the supply bottleneck, and youth unemployment. Despite rapid economic progress, the unemployment rate at 2.4 percent in 2017 among educated youth has remained at a higher trajectory at 10.6 percent in the age group of 15-24 years (National Population and Housing Census 2017). The capital-intensive growth cannot support the economy on a sustainable path of development.

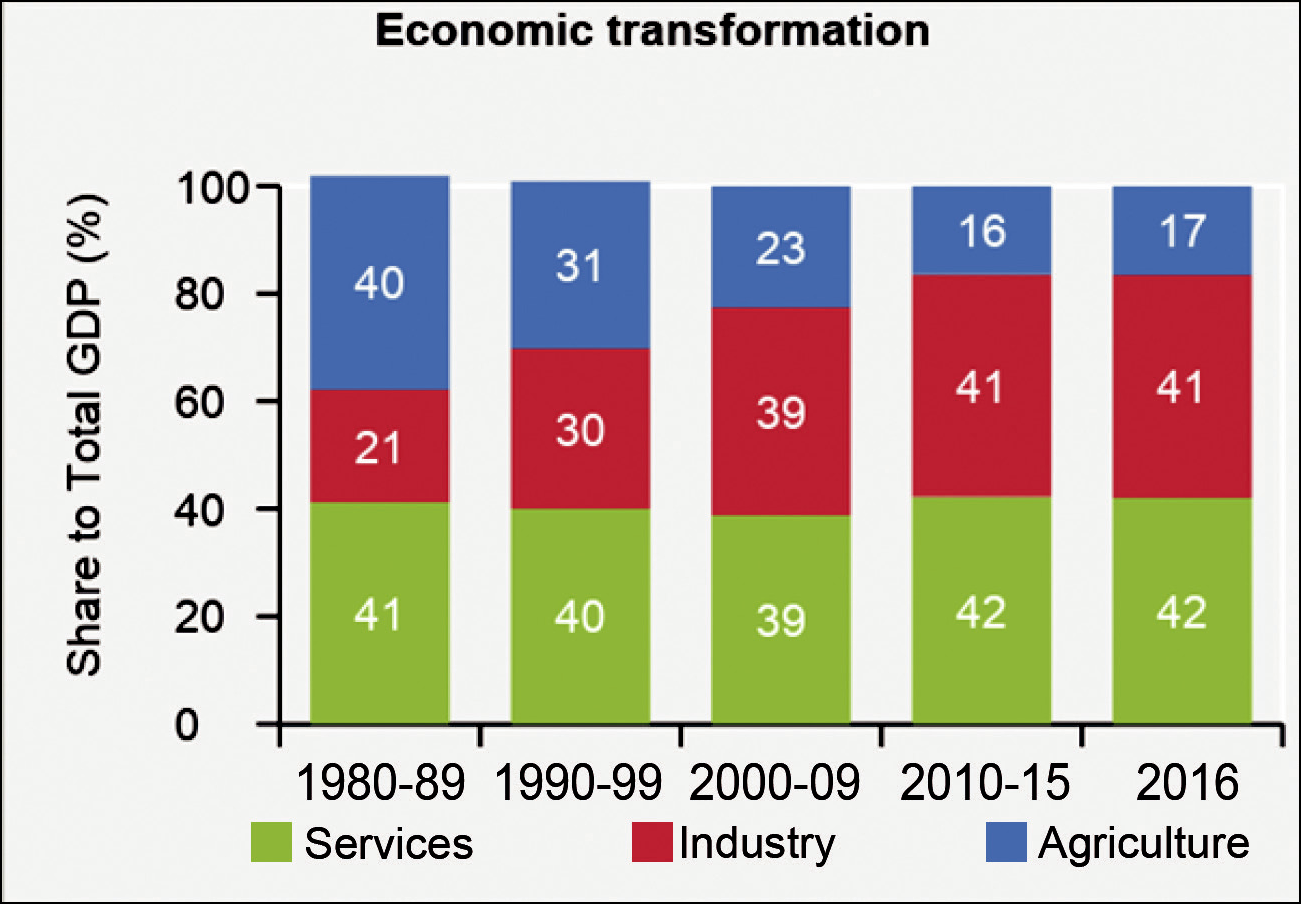

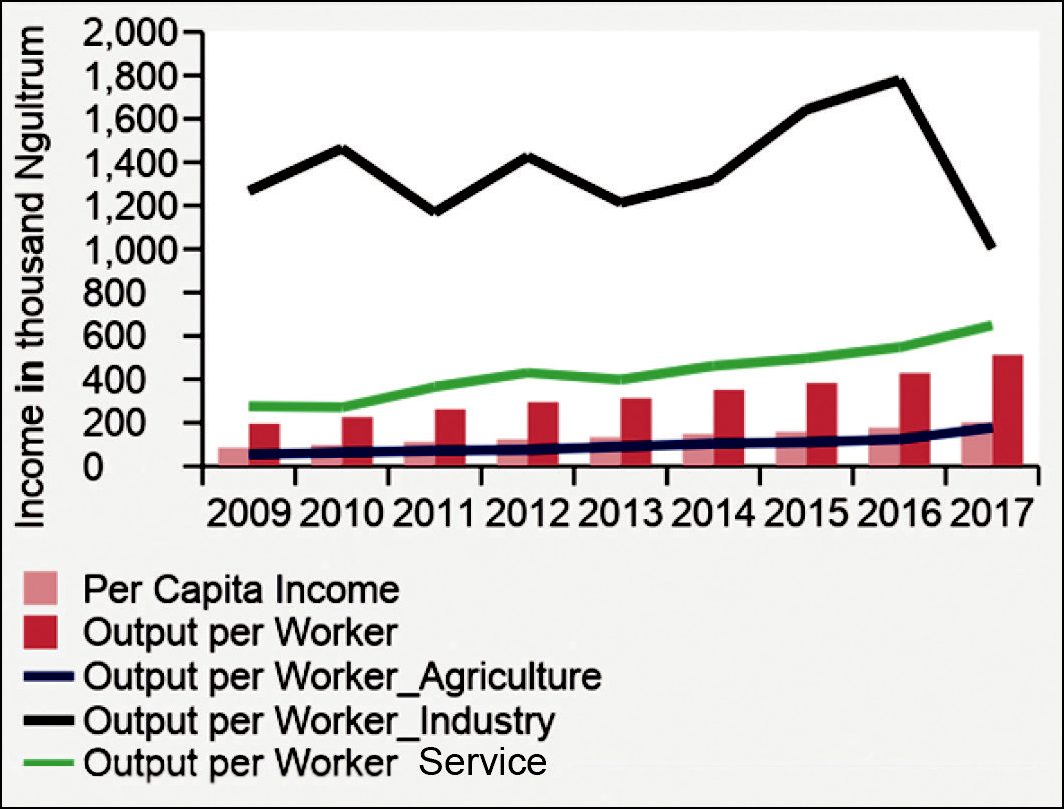

Data reveals that the main drivers of economic growth are dominated by the secondary and tertiary sectors which contribute almost 42 percent on average. The economy also relies on imports which include the basic necessities of life. For an agrarian economy, the agriculture sector’s contribution to GDP remains significantly low at 17 percent. Even in terms of labour force participation, it is surprising that over 50 percent is still employed in the agriculture sector. In the last four years, the average annual output per worker in agriculture is less than Nu 42,000, compared with Nu 663,450 and Nu 232,103 in the secondary and tertiary sectors respectively.

Coupled with these macroeconomic challenges, the distribution of national wealth has also been uneven. According to the Poverty Analysis Report 2017, a person at the top 20 percent of the total population consumes 6.7 times more than a person in the bottom 20 percent of the population on average. As of 2017, the Gini index for Bhutan stood at 0.38 and the poverty rate at 8.2 percent. It is estimated that one out of 12 individuals belongs to a household which has a per capita consumption below the poverty line of Nu 2,195.95 per month. Although Bhutan has made satisfactory improvement in bringing down the level of poverty, this is a matter of concern for the policy makers. As the economy attains a higher growth trajectory, disparity in national wealth distribution must not be uneven if the nation is to achieve balanced economic development.

For sustainable economic development, promoting entitlement and employment is the end and means to fulfil an individual’s economic choice. Economic freedom arises only when one is gainfully engaged in productive economic activities through employment. Gaining greater economic freedom by means of creating productive economic opportunities is the ultimate aim of human empowerment, leading the economy to a sustained path of economic prosperity. Bhutan must implement a national economic policy that will not only benefit the present generation but also open opportunities for the future generation to meaningfully contribute to the mainstream economic development process.

Economic Transformation: A Vehicle for Change

It is clear and concise that His Majesty’s vision to ensure a successful democratic transition, accompanied by successful economic transformation based on the foundations of a just, equal and harmonious society, translates into the need for greater national dialogue and commitment from the national policy makers.

Economic transformation does not just signify well-being or prosperity. It is more of creating a readiness and incentive for the market for change and development. Generally, the productivity growth characterises the process of transformation and the move from a traditional to a modern economy. Advancing innovation and technology is a precondition for modern development. Economic transformation must be a continuous process of enhancing labour and other important factors of production, for example, from the agriculture sector to manufacturing or to services. This movement of resources from lower productivity to higher productivity activities is a key driver of economic growth. Bhutan has a comparative advantage in human capital as well as other factors but we must be mindful that the transformation does not evolve naturally; it must be introduced through policy interventions such as economic diversification.

For Bhutan, promoting entrepreneurship and human capital, combined with modern technology, will be a catalyst tool for advancing economic transformation. More importantly, there is a need for an enabling institutional and regulatory environment for the market forces to act and react to the changing economic circumstances.

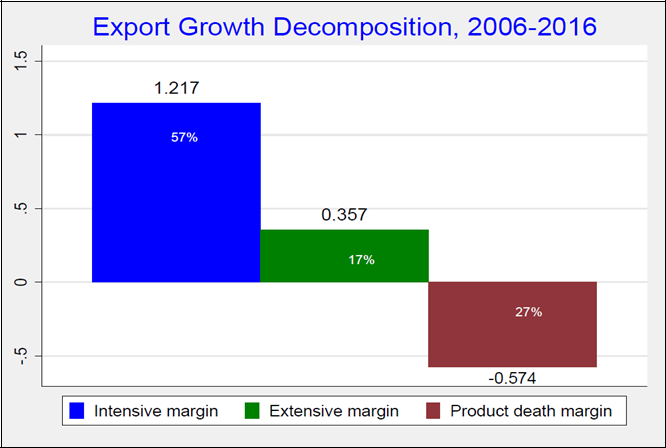

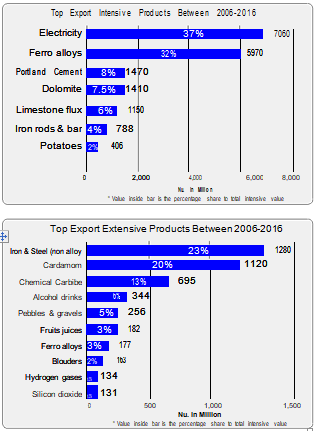

Diversification can occur across products, sectors, or trading partners, and often involves the shift to a more varied production structure through the introduction of new products or expansion and upgrading of existing products. Because of high production costs and the lack of economy of scale in many small developing countries, the introduction of new products (extensive export diversification) is generally difficult. Export diversification, therefore, happens mostly through the intensive margin in these economies, that is, through a more evenly balanced mix of existing export products or trading partners.

Likewise, for Bhutan, the intensive margin is estimated at 1.22 with an extensive margin of 0.35 and a product death margin at 0.57. This implies that Bhutan is highly dependent on electricity as an export commodity to a single market in India. Development and innovation of new products for export has been very limited, as indicated by extensive margin, and the rate of product extinction from the market remained high during the last 10 years.

Discovering New Sources of Economic Growth

In Bhutan, although we have categorically identified five Jewels as sources of economic growth — hydropower, cottage and small industries, mining, tourism and agriculture — the herculean task of transmuting these sectors into a functional engine of economic growth still remains. Too many national priorities are undesirable and often conflicting. We should re-prioritise the development need that will address our contemporary problems, and resolve the need of the hour. We must understand that, in the longer term, our economy will no longer be sustained only by a single sector, such as hydropower. It is necessary to capitalise on our available economic resources and complement the hydro-led economy through economic diversification. For Bhutan, economic diversification can be achieved through promotion of Cottage and Small Industries (CSI) sector. This sector will be the vital catalyst for attaining sustainable socio-economic development in the country.

We need to identify the nuts and bolts of the CSI sector. Institutional framework and policy specifications are important drivers that help the evolution and success in developing the CSI sector. We need to develop a range of programmes in diverse areas of CSI development, namely, e-financing, technology, innovation, managerial ability, market information, and developmental assistance, aimed at improving the working environment for CSIs. In the Bhutanese context, CSI development requires a crosscutting strategy that touches upon many areas, which can help the sector to improve and create a niche in the Bhutanese economy. Gaining from the experiences of other countries, Bhutan needs to suitably adapt its approach, policies and programmes for CSI development, and implement a set of measures to enhance the potential of this sector.

Given its merits and limitations, promotion of CSIs has been a recent buzz word in Bhutan. Reflecting on the 1960s, Bhutan has never optimally exploited its natural endowments and capabilities. In many sectors, Bhutan has comparative advantage in high-value low-volume niche market for economic growth. For example, tourism and natural resource based industries continue to be an area for exploration and business optimisation. It is opportune that the focus on the development of CSIs will complement His Majesty’s aspiration to create a just and a harmonious society, with equitable and inclusive distribution of the gains of development. Thus our first step towards economic diversification must be through the development of CSIs.

At a brief glance, Bhutan’s CSI sector is still underdeveloped. Currently, the CSI sector in Bhutan accounts for more than 90 percent of the total industries in Bhutan, with a total of 20,195 licensed and operational CSIs as of June, 2018. CSIs in Bhutan are categorised into three sectors — service, production and manufacturing and contract — with the service sector dominating the share of total CSIs at 78.9 percent.

Currently, the CSI sector is developing gradually but has been constrained by several problems and challenges, such as outdated technologies, low economies of scale, limited geographic connectivity with the regional and global markets, access to finance, homogeneous nature of industries and products and limited entrepreneurship and skills.

Recognising the impending challenges faced by the CSI sector, the government implemented the CSI policy 2012. The aim is to stimulate growth among the poor with equity and inclusion, promote balanced regional development, and help strengthen our rich cultural heritage. With the devil being in the details, the policy could not move the CSI sector. There was no significant pulse of the economic change with this new policy implementation. Many factors continued to suppress the progress of the CSI sector.

Necessary Interventions

One of the most prominent gaps that we see is the lack of an integrated and coordinated effort amongst the relevant government agencies and other key stakeholders. Every organisation is working in isolation and, even with initial coordination, there is no effort made to achieve the objective, leading to resource wastage. It is high time that all the relevant agencies look through one common lens with a national perspective where the multi-sectoral coordination and interventions to revamp the CSI eco-system become a priority. A solemn commitment of all stakeholders must be envisioned to achieve the national interest to uplift the well-being of the underprivileged sections of our community. As we now understand it, there are four key stumbling blocks that constrain the development of CSI ecosystem in Bhutan.

Access to Finance

Access to finance is often cited as one of the impeding factors for development of the CSI sector but it is not the only challenge faced by this sector. Generally, the CSI sector finds it difficult to access bank financing because of various factors such as lack of collateral security and asymmetric information between suppliers and seekers of funds. Some important financing strategies to support the CSI sector include development of credit information infrastructure to remedy the asymmetric information problem, utilisation of credit rating techniques, development of a sustainable credit guarantee scheme, development of specialised private banks for CSI financing, and introducing new sources of financing through equity, loans, angel investors, venture capital, crowdfunding, P2P, and trust funds. It is also vital that we look again into the aspects of risk management, through sustainable credit guarantee schemes, introduction of credit scoring and debt resolution mechanism, and reducing the regulatory barriers for the CSI sector. Moreover, the digitised platform and innovation in Information Technology provide a new avenue for a landlocked economy like Bhutan to harness the opportunities by overcoming all forms of constraints.

Entrepreneurship Development

Creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship are keys to economic growth. Studies have shown that young growth-oriented companies contribute to national competitiveness and job creation. One of the strategies by which the poor can escape poverty is by introducing new products and developing new business models. The CSI sector in Bhutan is characterised by low entrepreneurship capabilities and market information. There is a need to complement a dynamic ecosystem for CSI — both in agriculture and non-agriculture based economy — by promoting a culture of business oriented entrepreneurship in the country.

Human resource plays a critical role in promoting entrepreneurial skills. Bhutan’s ability to capitalise on young demographic dividends is still questionable when the country is faced with youth unemployment issues and continued dependence on expatriate workers. As shown by the 2017 Population and Housing Census of Bhutan, youth unemployment stands at 10.6 percent. The country’s working-age (15 years and above) population stands at 537,728 persons. Out of these, 340,236 persons (63.3 percent) are economically active, while the remaining 197,492 persons are economically inactive. They are the ones looking for the jobs in the capital city and other towns of the country. Overall, the country’s labour force participation rate is still lower at 63.3 percent.

Today, Bhutan has reached a critical juncture where our young working-age population has been steadily increasing, with the highest concentration in the 25-29 and 20-25 age groups, closely followed by younger age groups ranging from 15-19 and 10-14 years of age. It is critical for the country to gear up and find a sustainable way to engage these unemployed youths in productive activities, by creating a conducive environment to promote innovation through appropriate training, such as market-oriented technical and vocational skills and knowledge generating programmes.

Access to Technology

In certain cases, even when some individuals with high entrepreneurial capacity wish to set up a business, they are discouraged by the difficulties in access to affordable modern competitive technology. Public sector intervention becomes vital to bring a demonstration effect on the success of any CSI industry in the country, using an efficient technology. Generally, there are two ways in which the government could provide the access to technology. Firstly, a conducive policy and regulatory environment must exist. The current FDI policy does not promote the CSI sector. Conventional thinking on protecting the local industry from the threat of foreign investors becomes redundant with the rapid change in the nature of global trade and commerce. Making a paradigm shift in ideology to develop the CSI sector, using the international platform, is critical. Currently, no adequate efforts have been made to attract and bring in new technology, and technical know-how that will benefit the local business. There is a greater scope for bringing in newer technology, innovation and management practices that suit the local need.

On the other hand, collaboration and partnership with foreign partners will open new windows for promoting market access and also benefit from economies of scale. Firstly, both vertical and horizontal expansion of business is possible if we open the doors of the CSI sector to potential foreign partners, either bilaterally or multilaterally. Secondly, the government could also initiate support for local and state-owned companies to upgrade their technology with help from foreign partners.

Market Access

Although all of the four constraints are closely interlinked, interdependence of these constraints needs to be understood in the light of our local needs and comparative advantages. Bhutan is a small market with a limited population. Over the decades past economic development efforts on domestic products, for export or for internal purpose, did not grow. Rather, our dependency on external economies grew manifold. The development of a market is not automatic. It needs to be nurtured and there must exist an enabling environment both from the institutional as well as the regulatory front to help the market grow as the economy progresses over time. To cite a popular Say’s law of market (although modern economists challenge this) it provides new insights on the creation of a market of its own. To promote market access, whether it is domestic or foreign, demand must create its own supply.

The success of promoting market access depends largely on infrastructure, technology, and quality of the products. Today, the development of modern digital technology eradicated all the barriers of trade. We all now exist in a flat world. Bhutan is no more constrained by being landlocked, often cited as the prime barrier for trade and commerce. It is opportune for us to excel in harnessing the gains of a modern digital platform in the spheres of business and market expansion, using our pristine natural endowments and as a brand Bhutan.

Conclusion

A key to activate a strong relationship between growth and economic diversification rests upon policy and institutional factors. Economic diversification must be considered and calibrated in the context of a consistently planned economic development agenda. Improving the quality of infrastructure, human capital, and essential business services are essential for attracting investment and, in turn, fostering new economic sectors such as the CSI.

In these attempts, it is critically important to review our existing policies and institutional machineries that are linked intractably to CSI sector promotion. Obviously, an independent review of the existing CSI policy becomes a vital aspect of our exercise before we begin the journey of revamping and developing a conducive ecosystem for the CSI sector. It is also equally important to make a strategic vision on CSI and economic progress by learning from the international and regional experiences and best practices.

The Bhutan Economic Forum for Innovative Transformation (BEFIT) 2019, inspired by His Majesty’s vision of greater economic diversification, is a national platform that brings together a wide range of expertise to share best practices and discuss innovative solutions to emerging national and regional economic challenges. The overarching objective of transforming and bettering lives provides a good forum to review the CSI policy and come out with a concerted action plan.

Moreover, a collective effort is also required to address our common challenges and ensure that the benefits are shared equitably by all sections of our society. Often, the benefits of economic development do not touch the disadvantaged and vulnerable sections of the population. A special focus is recommended on these special groups to realise the aspiration and vision of His Majesty The King, an ultimate answer to address Bhutan’s economic challenges through economic diversification with the focus on revamping the CSI sector.