How Outsiders View Changes

Introduction

We are friends of Bhutan. Our feelings for the country go back 27 years. We were then residents in Bhutan and have worked there for various periods since then. In between longer stays we have visited Bhutan numerous times. We have travelled to every dzongkhag in the country and each of us has written articles and books about different aspects of the country.

Here is how we see what tourism was like in Bhutan in the early 1990s, when we both lived there, and the impact of tourism over the years.

Back in the 1990s, the tourism vision of Bhutan was “high value – low volume”. International tourists paid, in addition to USD 20 for visa, a fixed tariff of around 200 USD per day, of which 35 percent was government tax and the rest covered accommodation, food, guide, and transportation within Bhutan. So it was relatively expensive to be an international tourist in Bhutan. Regional tourists (mainly Indians) were exempted from paying visa fees and the tariff.

Bhutan received just about 5,000 international tourists annually when we first arrived, 27 years ago, and around 30,000 regional visitors, of which 50 percent supposedly were tourists. The number of regional visitors did not increase much over the next 15 years. In 2007, there were about 34,500 regional visitors of which about 17,350 were tourists. During the 15 years however, international tourism increased by more than 400 percent, reaching 21,100 international tourists in 20071.

In recent years, the increase in the volume of tourism has been dramatic. In 2018 (in rounded figures) Bhutan received 202,300 regional and 71,700 international visitors, totalling 274,000 visitors, of which 241,400 were tourists, and the rest — 32,600 persons — were on official visits, business people and families of people living in Bhutan. Of the 202,300 regional visitors, 178,000 were tourists. Indians constitute approximately 95 percent of the regional visitors.

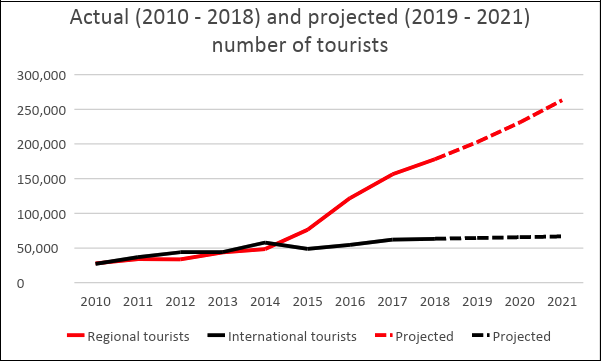

While the increase in international tourist numbers, from 2017 to 2018, has been moderate (1.8 percent), the growth in the number of regional tourists (13.9 percent) in the same period is alarming. If this trend continues unabated there will be 2,63,000 regional and 66,800 international tourists arriving in 2021. The table presents the alarming number of visitors by category (tourists, non-tourists, regional, international) between 2010 and 2018.

Table and figure – Source: Bhutan Tourism Monitor – the annual reports from 2010 to 2018.

| Visitors to Bhutan 2010 – 2018 | 2010 | 2014 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Regional tourists | 27.837 | 48.544 | 156.275 | 178.015 |

| Regional non-tourist visitors | 5.800 | 16.855 | 27.012 | 24.275 |

| Total regional visitors | 33.637 | 65.399 | 183.287 | 202.290 |

| International tourists | 27.196 | 57.934 | 62.272 | 63.367 |

| International non-tourist visitors | 1.267 | 10.147 | 9.145 | 8.440 |

| Total international visitors | 28.463 | 68.081 | 71.417 | 71.807 |

| Total tourists | 55.033 | 106.478 | 218.547 | 241.382 |

| Total non-tourist visitors | 7.067 | 27.002 | 36.157 | 32.715 |

| Total visitors | 62.100 | 133.480 | 254.704 | 274.097 |

Table and figure – Source: Bhutan Tourism Monitor – the annual reports from 2010 to 2018.

The tariff for international tourists has remained more or less unchanged during the past 20 years, so the increase of international and regional tourists reflects both global and regional wealth. Travel for leisure has become cheaper and more common and people, in particular Indians, richer. A trip to Bhutan has become more affordable to many people, as this posting on the Quora website tells:

“Bhutan is one of the most affordable and favourable destinations in the world. Unlike other countries, Bhutan doesn’t charge any extra fee for Indians visiting Bhutan. The total cost including Accommodation + Food + Cab [transport] will come around to 2–3K [2-3000 Indian Rupee] per person and will reduce to 2k on sharing basis”2.

Consequently, the “high value – low volume” policy has shifted to “ordinary value – high volume” for international tourists and to “extraordinary low value – extremely high volume” — and thus impact — for regional tourists. This development has happened without a policy and strategy to safeguard Bhutan’s unique culture and nature.

Bhutan 25 Years Ago

Imagine landing in Paro. When the BA 146 aircraft’s motor is switched off, and you have passed through immigration — individually or in very small groups — you cannot hear anything but birds singing, and perhaps some quiet conversation, and the occasional deep and gentle sound of a dung (longhorn) from far up in the mountains.

In Paro, and in your house or apartment in Thimphu, you will breathe in the cleanest and most breathtaking air your lungs have ever experienced. In the evening, you might walk to the town centre, enjoying the calm city, searching for a nice restaurant. It’s not a difficult choice, because there aren’t many restaurants and the quality is not the standard you are used to from your home country, but it’s ok, though your stomach sometimes may disagree.

After work, you may decide to take a small stroll up to Changangkha Lhakhang with your wife and kids, to light candles for your eldest daughter back home, trying to pass her exams. You are nearly on your own — no loud tourist crowd. It’s so calm — you feel Bhutan’s spirituality and culture, even though you are not a Buddhist.

In April and May, when the Etho Metho (Rhododendron) is in bloom, you decide to take a trek with a couple of your Bhutanese friends and kids. You do not want a difficult trek, so you contact a tour agent who recommends the Druk Path. When you camp at the shores of Bimmelang Tsho, you spot another small group on the other side of the lake, and local yak herders. But you can’t hear them.

Nothing disturbs you when you sit down with a cup of tea, enjoying the pristine nature, the clean environment and the company of your guide and the horsemen. You think of how lucky you are, being part of something unique and secluded, and that you are one of the fortunate few to experience this. You may decide to visit a nearby goemba (monastery). You are not alone, because there are one or two other tourists who, like you, quietly and with respect for the Buddhist culture, join the local pilgrims.

You are a pchilip, a “grey haired foreigner”, but you do not feel like a foreigner. You feel that you meet on equal terms with the Bhutanese, who enjoy meeting and talking with you.

“You have the watches — we have the time,” the Bhutanese said — 25 years ago — conveying the message that spiritual values were predominant in Bhutan, while material values reigned in our western part of the world.

Bhutan Today

The pristine nature is still there in the rural areas but, in many places, the scenario is adversely affected by ugly new buildings, including hotels, masses of tourists crowding for access to revered monasteries and polluting the place with noise and garbage. What we once experienced — very special and unique – that feeling has gone! The feeling of being part of something precious — that has also gone.

The uniqueness of trekking in small groups — enjoying nature, clean environment, and the relations with your guide and the horsemen — this has vanished. Groups of tourists trek along the same routes, visit the same places at the same time, so trekking routes and campsites are overcrowded, and there are signs of gross human behaviour everywhere.

Today it is impossible to visit monasteries and goembas quietly, respecting the Buddhist culture and monks in residence. Hordes of tourists visit the same sacred places at the same time, spoiling the tranquillity, like visiting an amusement park. Sacred places have become tourist attractions rather than places of worship.

If you are going up to Taktshang, you will have a tourist group just in front of you and another group at your heels. We hear that even Bhutanese hesitate to visit Taktshang these days — one of their most sacred places of worship.

If you visit Chhimi Lakhang — the place where one of us got our Bhutanese name, and to where Bhutanese couples with fertility problems used to come, where you could sit in peace and let your mind wander around the stories of the Divine Madman — it’s where tourists now flock. Guides entertain them with simplified stories of Dukpa Kuenley in Japanese, French and Chinese. We wonder: What do Bhutanese couples with fertility problems do these days?

Today we still have the watches but so do the Bhutanese… and now, do they have the time?

Conclusion

We acknowledge that there is a difficult balance between the expansion of the tourism sector that contributes to economic growth and creates employment — especially for the youth — and the adverse effect on society and the environment.

Mass tourism is not a unique problem to Bhutan. The massive impact can be seen in diverse places like Amsterdam, Venice, and Agra, and globally tourism will continue to rise. It is therefore important to identify precisely what are the core problems, and what steps Bhutan can take to mitigate those problems.

We opine that the core problem is that Bhutan now receives too many tourists, of which by far the most are regional tourists. We subscribe to what is said in the Bhutan Tourism Monitor Annual Report (2010):

“Bhutan continues with its philosophy of encouraging high-end, luxury tourism, with low environmental impact. It aims to become an exclusive destination that promotes culture, nature and wellness tourism. Bhutan has witnessed a terrific trajectory, reaching close to 41,000 tourists. 2010 has been a watershed year in the history of Bhutan, as the Royal Kingdom of Bhutan has taken great strides towards becoming one of the most attractive high-end tourist destinations in the world.”

But now (2019) it seems like the above vision is totally forgotten. The commercialism of tourism has taken over at the expense of the environment and culture of Bhutan. There is no doubt that the Bhutanese nature and culture are under pressure of being destroyed fast if nothing is done.

This development is linked to a gradual emergence of practices and behaviours that are very un-Bhutanese. Stories abound about tax evasion, where tourists pay cash and hoteliers give discounts because they can evade taxation, and where building permission and city services can be obtained in exchange for monetary or personal favours. Clearly, the integrity, morale, and ethical values which characterised Bhutan in the past are eroded.

A very relevant question is to what extent growing tourism affects Gross National Happiness (GNH) — positively and negatively. It appears that at least two pillars of GNH seem to be under pressure: preservation and promotion of culture and environmental conservation. It might be argued that these are the pillars that define the Bhutanese identity and the uniqueness of the country. It is therefore a worrisome trend.

Some Ideas to be Considered

We are aware that the development of a new tourist policy is under consideration. The work should be accelerated and a new strategy put in place. Lessons may also be learned from other places where mass tourism threatens to overwhelm local venues. At Taj Mahal in Agra, Indian authorities are considering introducing two caps: A maximum of 40,000 tourists a day (from currently about 70,000) and a maximum stay of three hours. In Amsterdam, authorities have introduced a “City in Balance” programme, halting buildings of new hotels and tourist shops, as well as an “enjoy and respect” campaign to influence tourist behaviour.3

It is obvious that the “high value – low volume” philosophy has no substance in the Bhutanese context as long as the majority (75 percent) of the tourists, i.e. the regional tourists, neither pays visa fees nor the tourist tariff.

How can this trend be mitigated? Would it be an idea to substitute the present tourist tariff system with a tourist tax levied on hotels for each stay of night per guest?

Should permission for constructions of new hotels be stopped? Should access to certain areas and sacred places be prohibited or limited?

There are, in fact, specific measures to safeguard the environment and the culture that could be instituted. Such measures could include rigid and robust control with trekking companies, as well as caps, and perhaps payments, for visits to monasteries for tourists. Moreover, training in the tourist industry must be reviewed, adjusted, and strengthened to cater for the present influx of tourist crowds as well as for new policies. Such measures could be put in place at short notice.

Our bottom line is that the very identity and the uniqueness of Bhutan and its main attractions are under threat. We hope that solid steps will be taken soon to craft a national policy and a tourism strategy that, when instituted, can stem the tide and preserve the unique nature and the unique culture of the country that we love.

References

1 Source: International Tourism Monitor, Annual Report 2007, Kingdom of Bhutan, Department of Tourism, Ministry of Economic Affairs (April 2008).2 https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-cost-per-day-in-Bhutan-for-Indian-tourists-and-what-are-the-best-places-in-Bhutan

3 https://www.iamexpat.nl/expat-info/dutch-expat-news/tourism-numbers-netherlands-set-ex-plode-29-million-2030